FROM THE EDITOR: Politics Are Increasingly Polarized; a Parking Lot Can Help Us Understand the Problem

As frustration with the political process grows, and more extreme voices demand ever-more-radical change, one UMW professor's approach to problem solving is showing a more effective path forward.

By Martin Davis

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Email Martin

The environment is one of those hot-button topics that tends to pit opposing parties against one another — tree lovers against developers, scientists again politicians.

The problem is that when opposing parties can’t interact constructively with one another, they stay in conflict. Hence, rather than finding solutions, the problems become wedge issues that are decided not by dialogue and compromise but by who’s in power.

In plain-speak, this is political “polarization.” A problem most are aware of, but few have a grasp of how to address.

John Tippett does.

As an adjunct professor of environmental science at the University of Mary Washington, he instructs his students in the science behind environmental dangers. And then he goes a step further.

I was lucky enough to observe his class on Thursday, when Tippett combined the science of managing stormwater run-off with teaching his students how to move beyond polarizing behavior toward effective, long-term change that benefits all parties.

It was a master class in wedding science and civics.

It Started with a Parking Lot

When it comes to protecting the Rappahannock River, one of the greatest challenges is managing rainwater run-off. Managing that requires being aware of two major contributors to the problem: 1) Air pollution, and 2) “hydrologically nonfunctional” surfaces that funnel pollution into the storm drains that then make their way to the river.

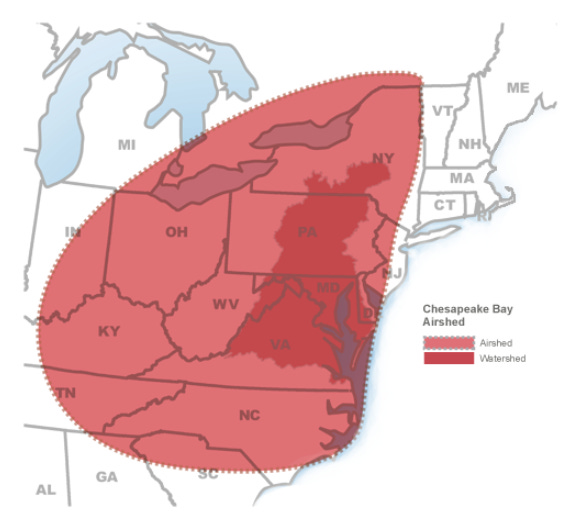

The air pollution problem stems from the Chesapeake Bay airshed, which brings particles from Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Upstate New York — all major coal burning locations — to our region.

As for hydrologically nonfunctional surfaces, there are few better examples than parking lots.

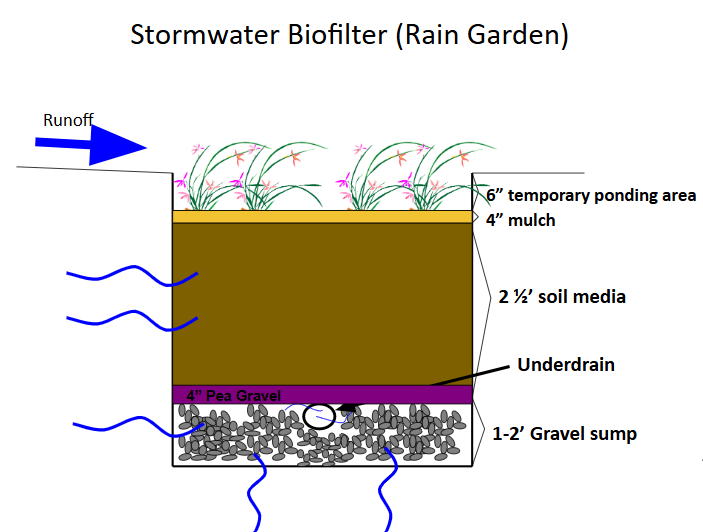

Fortunately, the science for solving the problem is fairly simple. Rain gardens are highly effective in filtering particles carried by rain, significantly reducing their impact on the river.

Before he was an adjunct professor at UMW, Tippett was the executive director at Friends for the Rappahannock. In that role he wanted to bring that easy-to-understand solution to the region. But how?

As he explained, it started with finding people to agree to be part of a model program. He found willing folks in a subdivision, where hydrologically nonfunctional ditches were carrying rainwater and its particles to the river.

The model was a huge hit with the residents who took part, and the visual impact was stunning.

The problem? It never grew beyond the demonstration project.

While Tippett traveled around the Chesapeake area training people in creating hydrologically functional spaces, went to lots of conferences, and oversaw a number of model projects, the problem itself remained.

Localities and builders working with tight budgets were reluctant to try something new without greater clarity about costs, time, and how it fits into local codes.

It was clear that bringing in a scientist to tell localities what to do didn’t work. Neither did writing books that sat on bookshelves or attending conferences where people get excited but give up at the first sign of resistance back home.

It Ended in Code Changes

As Tippett explained to his class, bringing about effective change requires something that is too often ignored — relationships.

These take time, of course. But Tippett learned that taking the time to invest in relationships is what finally moved the needle.

Simply said — whereas most of us want change now—understanding that significant change comes only through relationship-building and time is key to having a significant impact.

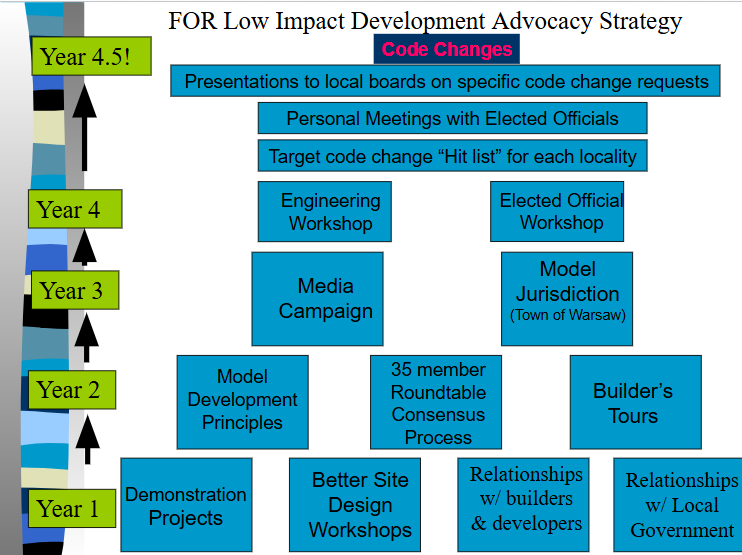

Over a period of four and a half years, Tippett took what he had started and then figured out what it would take to make meaningful change in how hydrology systems are developed.

He realized that to have effective change, he would need to work to reform the state codes that dictate how hydrology systems are built.

He pulled together a roundtable of stakeholders to discuss the idea and what would be amenable to all parties. He found a town to model the project, launched a meeting campaign, and then worked with engineers and elected officials on creating policies everyone could work with.

Once that was worked through, it became of question of deciding what local codes to targets and then working directly with political officials to bring about that change.

He knew he had something when, speaking before a board of supervisor’s member with a developer along side him, he heard the member say: I’m skeptical, but if the environmentalist and the developer are in together, I’ll go along.

A Civics Lesson for All

Beyond lessons in environmental science, Tippett was delivering a more profound lesson to his students — a lesson in civics.

Groups from across the political spectrum have rightly been decrying the decline of civics education in America for more than a decade. Often, they talk about correcting this decline in terms of altering or strengthening course offerings. (See these reports from the American Bar Association, the American Enterprise Institute, and Brookings.)

While classroom lessons are valuable, they are not as powerful as having people like Tippett who can draw upon their own experiences in effecting change through the democratic process.

Whether because of our impatience, our poor understanding of democratic principles, or our growing disconnection from one another, what has become obvious is that too many of us aren’t working through the democratic process as it was designed to work.

What Tippett is offering his students, and anyone who will listen, is proof that the democratic process can work. Changes take time, but when worked through, they are long-lasting and effective.

The key to all of it? Relationships, a sharply defined understanding of a given problem, and a willingness to take the time to see the work through.

Democracy, it seems, does still work — when we embrace the civics lesson Tippet is offering, and trust the process.

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit the link that follows.

Support Award-winning, Locally Focused Journalism

The FXBG Advance cuts through the talking points to deliver both incisive and informative news about the issues, people, and organizations that daily affect your life. And we do it in a multi-partisan format that has no equal in this region. Over the past year, our reporting was:

First to break the story of Stafford Board of Supervisors dismissing a citizen library board member for “misconduct,” without informing the citizen or explaining what the person allegedly did wrong.

First to explain falling water levels in the Rappahannock Canal.

First to detail controversial traffic numbers submitted by Stafford staff on the Buc-ee’s project

Our media group also offers the most-extensive election coverage in the region and regular columnists like:

And our newsroom is led by the most-experienced and most-awarded journalists in the region — Adele Uphaus (Managing Editor and multiple VPA award-winner) and Martin Davis (Editor-in-Chief, 2022 Opinion Writer of the Year in Virginia and more than 25 years reporting from around the country and the world).

For just $8 a month, you can help support top-flight journalism that puts people over policies.

Your contributions 100% support our journalists.

Help us as we continue to grow!

This article is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. It can be distributed for noncommercial purposes and must include the following: “Published with permission by FXBG Advance.”

"Democracy, it seems, does still work — when we embrace the civics lesson Tippet is offering, and trust the process."

Once again, a simplistic solution to a complex problem. Kumbaya, Michael row your boat ashore.

Yes, by all means, a practical means - but with a couple of givens that do not always apply, particularly in today's day and age. And are treating a symptom, while studiously ignoring the primary cause.

The givens. That we can all work together toward a beneficial goal. Yet it ignores some things. What if one side of the debate sees remaining in the debate stage AS the solution? They are not negotiating in good faith, but merely looking to use the process as a means of delay?

When one side - whether it be the tobacco industry, coal mine owners, pharmaceutical company, or in this case - a developer - or whoever it is who has a vested interest in blocking change is participating not to find a resolution, but to block a resolution.

What then?

Particularly when they are doing so, not as people, who can be arrested, have handcuffs placed on them, or be criminally liable - but rather are that false construct, a corporation - which according to our Republican Supreme Court - has all of the rights of a person, but none of the criminal responsibility - and can use money which is now classified as speech. And their goals are specifically to generate profit for shareholders with the least amount of cost without being locked up.

What then?

I would posit that too many of our "problems" come back to that basic process. Healthcare with gargantuan costs yet poor results.

Where your solution when Clay Jones has a stroke is not to question why we, the only one of the 32 richest OECD countries on this planet without guaranteed healthcare do not have guaranteed healthcare - but rather to urge us to contribute to a Go Fund Me page, because he's a great guy?

Not saying he isn't a great guy. But rather to question, as I suspect he would - based upon his drawings that I follow on bluesky, why that is our system?

Should he, or anyone else be reduced to begging in a Darwinian system of The Apprentice, where his rehab, housing, or family security is based upon how popular he is, how many friends, or how popular his views?

Someone said the other day that "charity" - like the soon to be upcoming celebration of our annual "giving" of a good meal at Thanksgiving to the homeless, is not really something to be celebrated.

But is rather an acknowledgement that we, as a society, have chosen - thorough our electoral choices to live in a society where we accept our citizens and their children not having the basic needs of survival.

Can't we do better?

Is contributing and celebrating such things helping, or merely perpetuating injustice, shortsightedness, and cruelty by pretending we don't?

I don't know the answers, but I sure wish we'd start asking instead of offering up placebos such as this as the solution.

And here - talking about bringing local stakeholders together to find a solution - yet ignoring the underlying cause. Someone is burning coal to the west of us, for profit - and we are suffering a cost as a result.

Why do we accept a system which allows that? Shouldn't capitalism be honest?

Rather than demanding these disparate groups come together and figure out how to bear the costs of mitigation - which again, is laudable; wouldn't it be wiser and more sustainable to demand better from those causing the harm?

Why are we not even allowed to ask? Or for that matter, demand? In a system where any legislator who does ask is attacked by lobbyists with unlimited power.

Again - you focus on the tree in front of you and ignore the forest.

In this particular instance - there are solutions. RGGI is a good example. One that was suspended by Virginia's Republican Party. It only addressed part of the harms, yet it was a start. Until they squashed it.

Will it be back? It should.

If you want honest capitalism - that creates a fair playing field between those making the money, and those bearing the costs - we need fundamental changes in our system.

Let's start with honest, fair, just competition - where all are welcome to make a profit, but not without accounting for the harms incurred in the process - not one that expects the ones incurring the harm to spend all of their energies figuring out the best way to clean up the mess caused by others.

Just some thoughts.... and I hope Mr Jones does well.