FROM THE EDITOR: Re-districting, the Seventh District, and the Reach of National Politics

The battle over Trump is disrupting congressional races across the country. The General Assembly is leveraging mid-cycle redistricting in that battle. Voters have a lot to consider before April.

By Martin Davis

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Email Martin

If there were any hopes that the debate over redistricting in Virginia would be nuanced and thoughtful, Sen. Ted Cruz (R - Texas) and Virginia State Sen. Louise Lucas (D - 18) swiftly ended them.

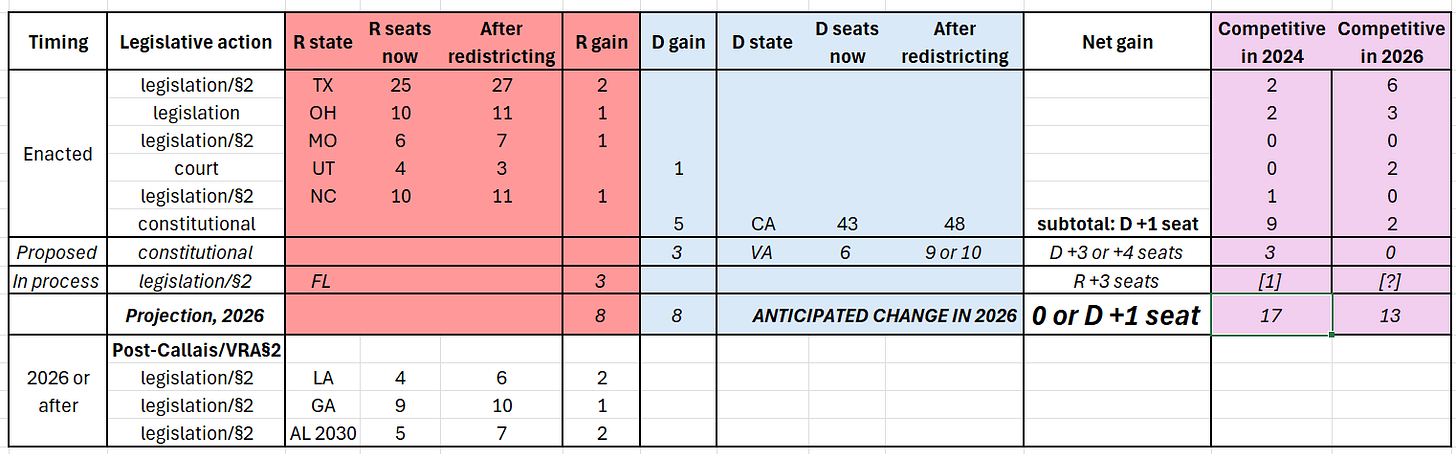

Cruz took to X to call out Virginia’s redistricting effort, which if passed would potentially give Democrats 10 of the state’s 11 congressional seats (the split is currently six Democrats and five Republicans).

A brazen abuse of power & an insult to democracy. 47% of VA voted Trump. They will now get just 9% of the seats. 52% of VA voters voted Harris. Now they get 91% of the seats.

Lucas shot back:

You all started it and we f[!@#]ing finished it.

Not exactly the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858.

As with bumper-sticker-style back-and-forths, the two are highlighting some interesting questions, and missing much of the meat of the matter. Should the new map become reality, voters in the current 7th Congressional District are going to experience significant change.

It’s important to understand these changes, but to fully understand them one needs to start at the national level and work down to the 7th.

Let’s dig in.

Starting it, Finishing it?

Lucas is certainly right that Donald Trump and Republicans in Texas started the push for mid-cycle redistricting. Historically, redistricting is done every 10 years on the heels of the decennial Census.

Texas, following the request of President Donald Trump, redrew its lines to ensure more districts in the Lone Star State go to Republicans. It’s a strategic move to try and ensure that Republicans don’t lose the midterm elections — something the president’s tanking popularity seems to make likely. Ohio, Missouri, Utah, and North Carolina have gone along with the ploy. Notably, the Republican-controlled Indiana state legislature rejected redistricting.

In response, California and now Virginia are trying to counterbalance the Republican pick-ups by redistricting to give Democrats more seats in their states.

Despite Lucas’ assertion, however, Virginia’s redistricting doesn’t finish the battle. In fact, if successful the best it would do is reset things to where they currently stand.

That’s the conclusion of Samuel Wang, who directs the Gerrymandering Project at Princeton University and writes the Fixing Bugs in Democracy blog.

In a January 20 post, he noted that should seats flip according to the newly gerrymandered state congressional districts, the result would essentially be a wash. Republicans are projected to pick up 8 seats should Florida push through its redrawn map, while Democrats will also pick up 8 seats.

“This is the cost of partisan gerrymandering,” Wang wrote: “little net benefit to either major party, but considerably reduced competition.”

Virginia’s map, however, is hardly a done deal.

Before any lines are officially drawn, Kyle Kondik — director of communications at the Center of Politics — told the Advance via email, “the Supreme Court of Virginia and, then, the voters will each have their say before this map goes into effect.”

Should it get struck down at either of those stops, Lucas and the Democrats will have roiled up a lot of political anger for no real gain. Something that could potentially bite the Democrats at a later date.

A big risk given that it seems apparent that Democrats are likely to pick up at least two seats in November even without redistricting.

As evidenced in last November’s elections, Democrats are energized and turning out in large numbers that are translating in big gains in state legislatures — we saw it here in Virginia, as well as in New Jersey, in November.

It’s clear that that momentum is not waning. A series of recent special elections in Texas and Louisiana had Democrats winning seats where Trump had comfortably won just a year earlier, showing that the frustration with the current direction of the country under the president is growing. And voters are making that displeasure known.

Given Trump’s chaotic style and likely ongoing dismissal of voter concerns about affordability, the deployment of ICE, and his dismantling world alliances, voters’ frustration isn’t likely to improve.

Consequently, prognosticators like the site 270toWin and the Cook Political Report are seeing clear indications that Republicans are going to lose their majority in the House in November. And predictive markets like Kalshi are even more bullish on Democrats winning back the House.

Not How Redistricting is Done

Cruz’s main argument suggests that Congressional redistricting should reflect how people voted in the most recent presidential election. It’s a clever emotional trick, but detached from the realities of how re-districting is supposed to work.

There is no one perfect way to draw congressional districts, and states vary in the factors that they take into consideration.

Nonetheless, the National Conference of State Legislatures has identified six “traditional principles” that states tend to follow when redrawing lines.

Compactness: Based largely on a district’s physical shape and on the distance between all parts of a district. A circle is a perfectly compact district under most measures.

Contiguity: All parts of a district are connected. States sometimes make exceptions for parts of a district separated by water.

Preservation of counties and other political subdivisions: Districts do not cross county, city, town or other municipal boundaries.

Preservation of communities of interest: Geographic areas, such as neighborhoods of a city or regions of a state, where residents have common political interests that may not coincide with the boundaries of a political subdivision.

Core preservation: Maintain the cores of previous districts to the extent possible. This can result in incumbent protection and similar maps from cycle to cycle.

Avoiding incumbent pairing: Avoid moving multiple incumbents into the same district.

Notably absent from this list? How people voted in the most-recent presidential election.

Cruz tries to argue that Republicans are the ones most hurt by the new map. In fact, it affects all Virginians through a process called “displacement.”

Redistricting by definition results in the displacement of voters — i.e., voters are either redrawn into a new congressional district, or they will pick up a new legislator.

This disruption, Wang contends, is a good measure of how gerrymandered a state has become.

“As documented for Ohio, Texas, and California,” he writes, “an aggressively partisan map can typically displace one-third of voters. Those voters are guaranteed to get new representatives who do not necessarily know their priorities or needs. And in a partisan gerrymander, voters get a new representative even if they haven’t been moved.”

The Virginia map being considered is likely to be far more partisan.

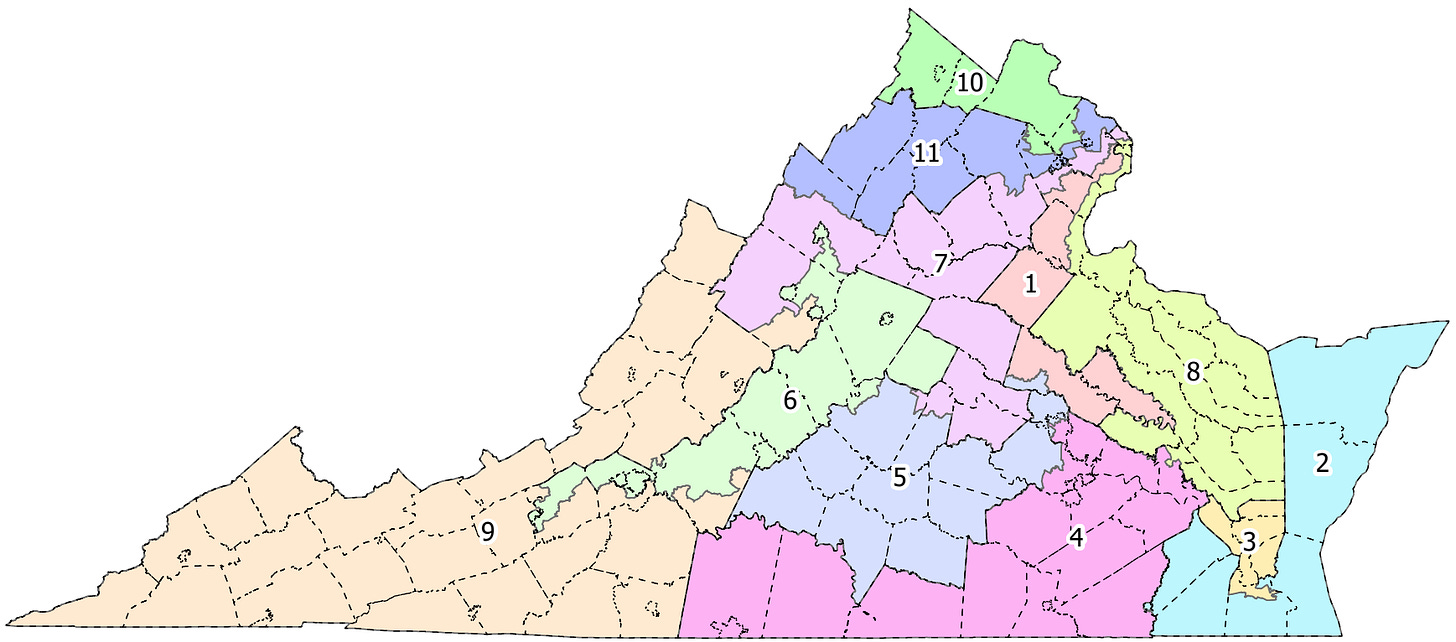

Using a tool called Dave’s Redistricting, interested people can map out possible congressional maps and measure how those changes will affect displacement — among other matters.

Wang and his team at the Electoral Innovation Lab — a nonprofit he also leads that is unaffiliated with Princeton University — have run several scenarios that would get Virginia to a 10 Democrat, 1 Republican map. The resulting displacements speak for themselves.

To get to an 8 - 3 Democrat-leaning map, around 12% of Virginians would be moved into a new district and about 22% would have a new representative.

Modeling for a 10 - 1 map would move 44% of Virginians into a new district and give 62% a new representative.

The model doesn’t match the map currently being considered perfectly, but it does give an idea of the disruption that is sure to result from any 10-1 map.

What it All Means for the 7th

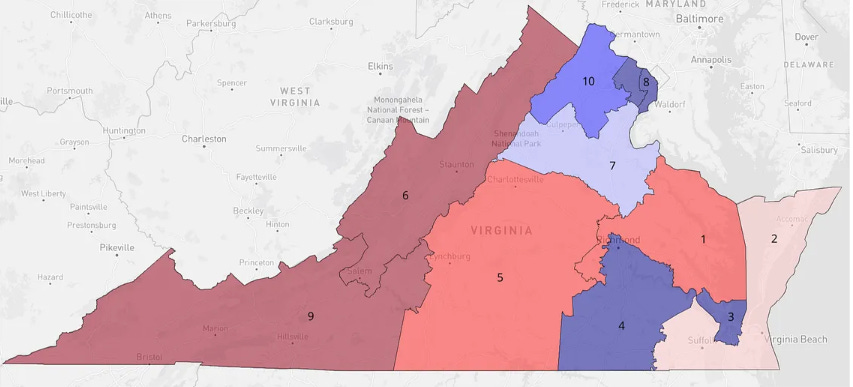

Displacement will be a major issue for what is now the 7th District. What is currently a compact, contiguous, competitive district will be broken up into 3 non-compact districts that are oriented north and south, ending compactness and breaking up voters in counties — particularly those in Prince William, Fairfax, and the Richmond suburbs — to create Democratic majority districts.

Spotsylvania, Fredericksburg, and parts of Stafford would be grouped together into the new 1st Congressional District that would run south to Hanover and King William County and north to include parts of Prince William and Fairfax.

Caroline and King George would form part of a new 8th Congressional District and would run south through Westmoreland, Warsaw, and Gloucester, among other localities, and extend north to include parts of Stafford, Prince William, and Fairfax.

Orange County would be pulled into a new 7th Congressional District that runs from the western Richmond suburbs and north to parts of Fairfax.

When the 7th Congressional District was last redrawn to create the current district, the locus of power shifted from Richmond to Dale City. In the proposed new map, Northern Virginia would pull considerably more sway in each of the new 1st, 7th, and 8th districts.

So egregious is this gerrymandering that it would likely move Virginia from what the Gerrymandering Project had previously rated one of the most-balanced maps in the country to one of the least balanced.

How will this potentially affect voters in the current 7th District beyond displacement?

On the plus side, it could give the region more power. Kondik told the Advance that: “One could argue that having more members representing a certain area might actually give the area more clout as opposed to less, although I am honestly not sure if that's actually true or not.” That could be important for our region, which is the fastest growing in Virginia.

Rather than one member of Congress arguing for the region’s needs, there would be three.

It’s also notable that this map would expire in 2030 and revert back to the map Virginia currently enjoys. Presumably, this districting would be set to expire after Trump is out of office and hopefully ending the need for gerrymandering.

However, 2030 also marks the next Census, meaning the new map would expire at the moment redistricting is again beginning.

And herein lies is the risk for Democrats.

Power shifts regularly. Should Republicans regain the General Assembly in 2030 or the governorship, don’t be surprised if Virginia’s 10-1 Democrat advantage in 2027 becomes a 10-1 Republican advantage in 2032.

Right, Wrong, Democracy

There is plenty of blame to go around for the current redistricting push.

Had Trump and Texas decided against gaming the November midterms because they fear — rightly is seems — that a blue wave is coming, Virginia would likely have stayed with its current six Democrat, five Republican map.

Further. assuming the last election was no fluke — and increasingly that doesn’t look to be the case — Democrats probably pick up at least two seats, and possibly three, this November without redistricting.

So why the aggressive redistricting?

Part of the answer lies in giving Trump and MAGA supporters a taste of their own medicine. Have power? Push it to the max. That’s what Trump and MAGA have shamelessly been doing since January 20, 2025. Lucas and Speaker of the House of Delegates Don Scott (D -88) are giving it back to the president. Revenge is not the best of reasons to radically redraw lines.

Another part of the answer lies in the fact that since 1994, when Newt Gingrich made nationalizing congressional elections the key to victory, America has been on a course to do precisely what is happening now.

The focus of members of the U.S. House of Representatives was from the founding meant to be on those citizens they represent at the state level, not the desires of the executive office or national political leadership.

Texas, Ohio, North Carolina, Utah, Florida, California, and now Virginia are acting in response to national leadership — not the voices of the people the members represent.

Playing the blame-game, in other words, won’t fix this problem.

What will is stepping back and striving for balance in our political processes.

Wang said it best. “A better outcome would be a cease-fire.”

Virginia’s Supreme Court and the state’s voters will decide if a cease-fire is possible here.

At least here, the voters — and not the politicians — will make that decision.

Voters have a lot to weigh before going to the polls.

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit the link that follows.