SPECIAL REPORT: 'You See Them, but You Don't See Them'

Mayfield is shaped by two issues it never asked for - a pipeline and a railroad. Its residents are leading the charge to right old wrongs and make the community safe for those who live there.

By Adele Uphaus

MANAGING EDITOR AND CORRESPONDENT

Email Adele

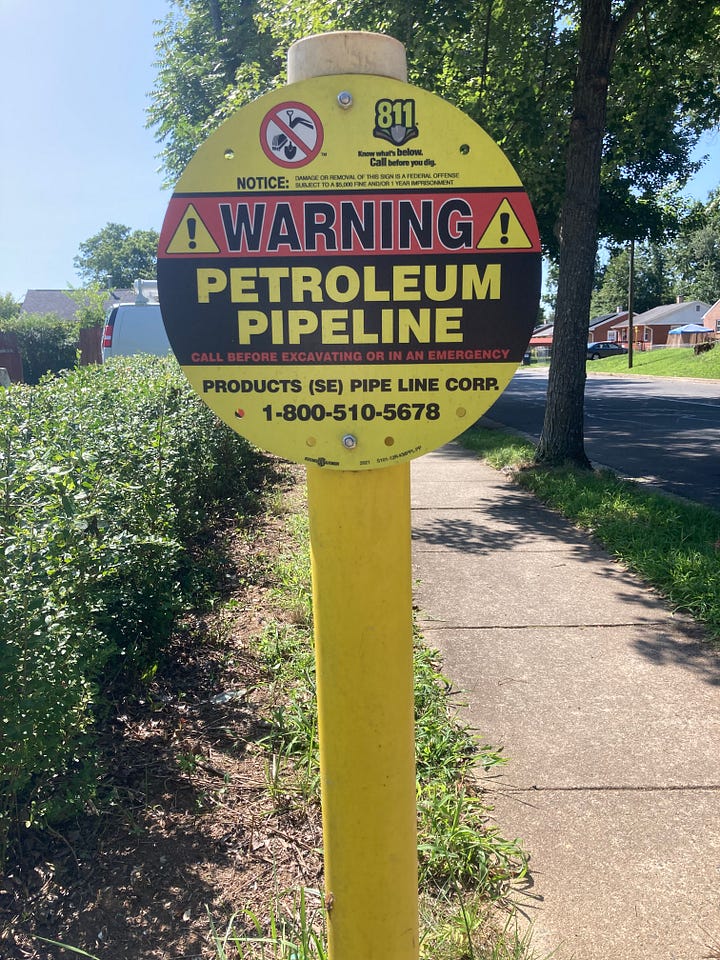

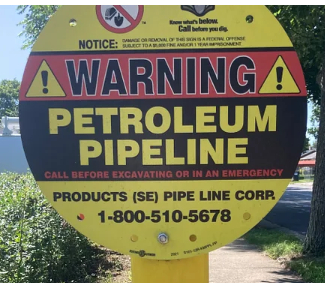

If you’re walking along certain streets in Fredericksburg’s Mayfield neighborhood, you might notice a round yellow sign, standing about waist high.

Once one catches your eye, you’ll likely notice another a little further down the street, and then another, and then another.

“Warning!” the signs read. “Petroleum Pipeline. Call before excavating or in an emergency.”

These signs, or others like them, have been in the neighborhood since 1964, when the Plantation Pipeline Company laid down an extension of an existing pipeline carrying gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel from the Gulf Coast to businesses along the east coast.

For residents of Mayfield—many of whom grew up in the neighborhood—the signs are part of the everyday landscape.

Grownups recall that as children, they played around the signs posted near where the train tracks run through the neighborhood and never thought about what they said.

“You see them, but you don’t see them,” said Trudy Smith, a lifelong Mayfield resident and president of the civic association. “No one ever questioned them or knew what they were.”

But now, residents are wondering why there isn’t widespread knowledge about a pipeline carrying flammable, hazardous substances that runs three feet beneath their front yards. They’re wondering why, over the decades, they were never provided with information about the pipeline, its contents, and potential dangers—and why the pipeline has to run through their community in the first place.

Since this past November, residents and members of the Fredericksburg chapter of the NAACP have been looking for answers.

“We’ve been doing research to figure out why people didn’t know,” said Sabrina Johnson, chair of the Fredericksburg NAACP’s environmental and climate justice committee. “This is why environmental justice exists. This is the purpose of environmental justice work.”

‘Don’t question it’

The 3,100-mile pipeline—originally known as the Plantation Pipeline and now called the Products (SE) Pipeline—originates near Baton Rouge, Louisiana. It is capable of delivering approximately 720,000 barrels per day of gasoline and serves the metropolitan areas of Birmingham, Alabama; Atlanta, Georgia; Charlotte, North Carolina; and Washington, D.C.

It began operating in 1942 and was extended from Richmond to Alexandria in 1964.

For most of its journey through Virginia, the pipeline runs within the CSX railway right-of-way and is not close to any homes, Fredericksburg Fire Chief Mike Jones said.

Mayfield, a majority-minority neighborhood that dates to the early 1900s, is one of the very few residential communities that the pipeline transects as it travels through the Fredericksburg area.

“It was just, ‘Don’t question it,’” [Mayfield resident Hashmel] Turner said of decisions made that affected the neighborhood.

The only other residential community that is close to the pipeline is a portion of the community off Primmer House Road in Stafford County, Jones said.

The Free Lance-Star announced in January of 1964 that the pipeline was coming to the area.

In April of that year, the newspaper reported that the route would “follow the RF&P Railroad right of way.” An engineer with Plantation Pipeline Company told the paper that a shipment of 12-inch pipe had been ordered from Bethlehem Steel and that it would be coated with “asphalt tar with fiberglass reinforcing, surrounded by an outside wrapping of asbestos felt.”

In May 1964, the paper reported that City Council would consider a request from the pipeline company to build the pipeline on city property.

“The line’s proposed route through the city includes two Airport subdivision streets before crossing U.S. 17,” a May 14, 1964, article states.

According to City Council minutes, Council referred the request to the Streets Committee. On June 9, the committee recommended approval of the request and Council approved an agreement with the pipeline company, granting it “permission to use certain streets for construction, reconstruction, repair, maintenance, and operation of 12 ¾ inch pipe.”

The agreement stated that construction and operation of the pipeline must be “done in a manner satisfactory to the city manager.”

There’s no record of residents being consulted or given the opportunity to provide input into whether they wanted a pipeline to run under the streets in front of their houses.

“People are busy working, putting bread on the table,” Smith said. “It escapes their notice, especially when no one brings attention to it.”

Hashmel Turner—a lifelong resident of Mayfield, former City Councilor, and local pastor—said politics around race in the 1960s cast “a cloud of fear” over the city’s low-income, Black and brown neighborhoods.

“It was just, ‘Don’t question it,’” Turner said of decisions made that affected the neighborhood.

A newspaper archive search reveals a handful of incidents affecting the Plantation Pipeline since it was installed in Virginia, but none in Mayfield.

In 1977, a pipeline break near Quantico spilled “between 5,000 and 10,000 gallons of fuel oil” into the Potomac River. In 1984, according to the Free Lance-Star, a section of the line near Ladysmith, in Caroline County, leaked, “spewing a mist of gasoline” into the air.

There’s no record of residents being consulted [by the city council in 1964] or given the opportunity to provide input into whether they wanted a pipeline to run under the streets in front of their houses.

In 1987, also in Caroline, a work crew burning the remains of a house ruptured a section of the pipeline, “sending flames leaping 100 feet or more into the air and causing the evacuation of eight to 10 nearby homes.”

‘We are learning together’

In November of 2023, a Mayfield resident was out walking and noticed work crews digging at the site of one of the yellow warning signs.

She reached out to Johnson to find out what the workers were doing. That led to months of research and conversations with city government, the fire department, and Kinder Morgan, the Texas-based company that, since 2000, has operated and partially owns the pipeline.

“In some ways, it feels like we are learning together,” Johnson said.

After an inquiry from city government, Kinder Morgan told City Manager Tim Baroody in January that the company had been conducting “integrity maintenance” on the sections of pipeline in Mayfield “through the use of internal inspection tools.”

“When an anomaly of concern is identified, our crews and contractors are dispatched to inspect the pipe and determine the corrective action, if any, to ensure the safe operations of our pipeline,” Ken Collins, Kinder Morgan’s public affairs director, told Baroody in the letter, which was shared with the Advance. “Typically, these investigations and repairs take minimal time and disturbance, such as three to four days.”

The Advance asked Kinder Morgan … how many Mayfield households receive pipeline information and if the company has and can provide records of a regular public awareness campaign in the neighborhood, and did not receive a response.

The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, or PHMSA, which operates under the federal Department of Transportation, regulates the network of pipelines that transport hazardous materials across the country.

The administration was created in 2004. Before that, Johnson said, “pipelines were largely unregulated.”

Federal pipeline safety regulations require operators such as Kinder Morgan to develop and implement public awareness programs that follow recommendations developed by the American Petroleum Institute in 2003 and updated in 2010 and 2023.

According to the recommendations, residents “located along transmission pipeline right of way[s]” should receive “baseline messages” every two years. The messages should make residents aware of the pipeline, potential hazards, damage prevention, how to recognize leaks, and the crucial importance of calling 811 before digging anywhere near the pipeline.

“Supplemental messaging” can include the operator’s “integrity management plan, right of way encroachment prevention, [and] any planned major maintenance/construction activity.”

Johnson said the Fredericksburg NAACP and the Mayfield Civic Association attempted to determine whether Kinder Morgan has been providing the required messaging every two years. She said the Virginia State Corporation Commission, PHMSA’s inspection agent in Virginia for the activities of companies like Kinder Morgan, reviewed the company’s activity and could find “no record of noncompliance.”

Johnson also noted that PHMSA advised that the owner/operator “is not responsible for whether folks read or understand what they receive.”

And for Smith, it’s “not enough” that the required public notice only goes to the handful of households located directly on the pipeline right-of-way.

“Everybody [in Mayfield] should receive notice,” she said. “The pipeline is only in one section of Mayfield—the other section never knew anything about it.”

According to safety information provided by the city, the local NAACP, and the Civic Association, if there were to be a leak, spill, or other incident, the entire community of Mayfield is in a potential evacuation zone.

The Advance asked Kinder Morgan last week how many Mayfield households receive pipeline information and if the company has provided and can provide records of a regular public awareness campaign in the neighborhood; it has not received a response.

‘We can do better’

Johnson and Smith said Kinder Morgan’s representatives have informed them that Mayfield “is now on their radar,” and Fredericksburg City has also committed to providing regular, ongoing information to the community about the pipeline, its operations, and incident response plans.

In July, Fire Chief Jones gave a thorough and transparent presentation about the pipeline to a “standing room only” crowd at a meeting of the Mayfield Civic Association, Smith said.

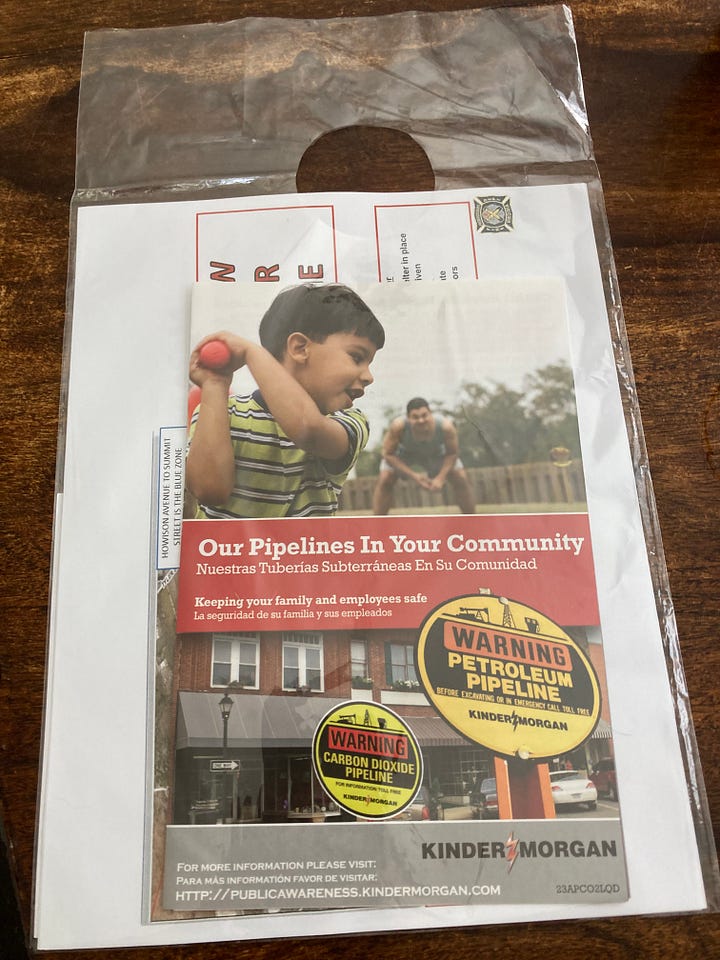

Earlier this month, the Fredericksburg NAACP, the Civic Association, and the fire department canvassed the entire neighborhood, handing out brochures in both English and Spanish about the pipeline and evacuation plans.

“The next step is to get back together after the National elections in November and discuss next steps on how to provide timely and regular updates on the pipeline to the community,” Jones told the Advance. “The Fire Department wants to provide an all-encompassing update on all actions of the Fire Department and a safety message to the Civic Association at least once a year.”

Johnson said the city’s commitment to the neighborhood has been, “We can do better than [what the federal government requires.]”

“This has to become part of the required protocol,” she said. “That’s going to be extremely important going forward.”

Right now, Fredericksburg is in the process of updating its ten-year Comprehensive Plan, and Johnson said the local NAACP hopes the planning process will include reflection on how inequities such as the pipeline occur.

“[Planners should ask], ‘Are we hearing from folks in a meaningful way?’” Johnson said. “What do we already understand about any disproportionate adverse impact of city policies and practices in our community? The more they know going into the process, the better the outcomes for all as we plan for the future.”

It’s About More Than a Pipeline

The pipeline isn’t the only conduit of hazardous materials that runs through Mayfield. The July derailment of five CSX tanker cars into a soundwall at Cobblestone Square apartments, near Mayfield, has renewed attention to the fact that tanker cars storing hazardous material are sometimes parked in the CSX railyard behind the neighborhood, and that trains transporting these materials travel through the neighborhood on a daily basis.

“We’re in a wedge,” said Smith. “We have hazardous materials running under our streets and backyards, and the railroad where hazardous materials are stored. It’s everywhere you go.”

What Smith really wants—even though she said she knows it’s unrealistic—is for Kinder Morgan to take the pipeline out.

“They put it in. They can take it out,” she said.

Smith is grateful for the city’s commitment to providing regular, ongoing education and information about the pipeline. But that won’t stop her from worrying about her elderly, housebound neighbors and what will happen to them in case an evacuation is mandated.

“We’re in a wedge,” said Smith. “We have hazardous materials running under our streets and backyards, and the railroad where hazardous materials are stored. It’s everywhere you go.”

“This community is vulnerable,” she said. “There are many people who can’t evacuate. It’s like a frog sitting in a pot waiting to be boiled.”

And even if the pipeline is never compromised, residents of the neighborhood will always have to live with the potential that it could rupture or fail.

“The constant exposure to environmental risks and hazards that other communities don’t have to bear has significant long-term negative effects, including on health, economics and other general quality of life conditions,” Johnson said.

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit our website at the link that follows.

Support Award-winning, Locally Focused Journalism

The FXBG Advance cuts through the talking points to deliver both incisive and informative news about the issues, people, and organizations that daily affect your life. And we do it in a multi-partisan format that has no equal in this region. Over the past month, our reporting was:

First to report on a Spotsylvania School teacher arrested for bringing drugs onto campus.

First to report on new facility fees leveled by MWHC on patient bills.

First to detail controversial traffic numbers submitted by Stafford staff on the Buc-ee’s project

Provided extensive coverage of the cellphone bans that are sweeping local school districts.

And so much more, like Clay Jones, Drew Gallagher, Hank Silverberg, and more.

For just $8 a month, you can help support top-flight journalism that puts people over policies.

Your contributions 100% support our journalists.

Help us as we continue to grow!

Thank you for solid reporting on our city. I learned a lot in this piece — though I’ve been a resident for 36 years. Let’s undo past wrongs and protect our beloved community.

Mayfield has another issue it never asked for besides a pipeline and a railroad . At the request of the City Manager and City Council the Industrial Park at the edge of their community is being looked at for a Data Center. So along with pipeline and tankers full of hazardous materials they may be looking at 24 hour a day humming/vibration and the smell of diesel from huge generators needed to support this Data Center.