Riverside's To Kill a Mockingbird Wrestles with Heroes and Our Failure to Live Up to Their Ideals

By Dennis Wemm

THEATRE CRITIC

By Christopher Sergel, adapted from the novel by Harper Lee

Presented by Riverside Center for the Performing Arts

American classics are a unique branch of drama. They are parables that both sing the praises of a hero with strong values and are a display of how the country doesn’t live up to those values. The values are supposed to govern its lives and policy. Frequently the decisions are made in courtrooms due to the often life and death nature of the decisions. Such a play is To Kill a Mockingbird adapted from a novel by Harper Lee.

(Note: for those interested a summary of the play’s production history is included in the TLDR section at the bottom of this review.)

Riverside’s production of the play is intense without being violent, value-driven but not prescriptive, fascinating, and heartfelt. Seeing it a few days after opening was a powerful evocation of the ideals that drove the Civil Rights movement of the 50s and 60s. It was also a reaffirmation of those ideals in the face of the modern world.

It is not preachy but it is a strong reminder of how things were before and how far we have to go to live up to our goals. It presents the human side of racial injustice by presenting us with a central character who is principled and unafraid, whose goal is to protect everyone who seeks his aid. On a personal scale it’s also the story of a family and how we teach our children what we must do to protect everyone who needs our help. On a social scale it is a scathing reflection on how prejudiced people, if given permission to act, will only desist if they are confronted with their own humanity and that of their intended victim.

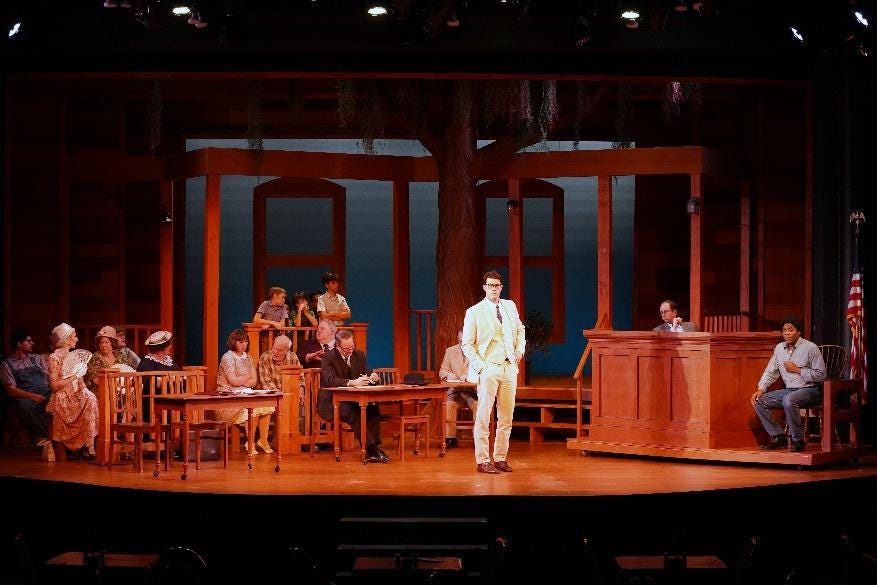

At Riverside, the majority of the play is shared out with the audience, meaning that the actors are not standing in profile speaking directly with each other, but deliberately talking out to the audience throughout the scene. This lends to a strong payoff in the climactic courtroom scene, where the audience becomes the jury, receiving the final arguments from the attorneys Atticus Finch (Tug Coker) and Mr. Gilmer (Andy Braden as a principled by-the-book public prosecutor who is a strong voice for the 1935 southern status quo).

The trial is set up strongly, and has long been a model for courtroom dramas with a conscience ever since the movie first opened in 1962.

In this production the young characters are portrayed by kids whose age roughly matches that of their characters. This works well for the production, since the dialogue in the play shows a “good ear” for how children would have sounded in the past. The young actors have clear voices and show an obvious understanding of their roles.

A further aspect of American classic theatre is that the stage is populated by characters who together form a kind of Greek chorus, commenting on the action and questioning the central characters. They act as an ordinary society whose influence forms a kind of alternative picture of how people should act. Sometimes positive, sometimes neutral and self-interested, and sometimes downright ugly in action. In Mockingbird we see an entire spectrum of action. As long as our central character, Atticus, has a say in the events of the plot they seem to be, if not reasonable at least limited in direct action. When we are caught in the machinery of justice and punishment and good no longer has an influence-in a jury room or a prison yard-the ugly sides always seem to win the day.

The production supports the action of the play truly well. As I mentioned before, the costumes are accurate for the characters and evoke a feeling of nostalgia: they are accurate to the 1935 time period of the show. They are also in some way timeless and perfect for the characters wearing them. The cut and fit were impeccable (other than what seemed to be a slippery wig). Seeing a pair of shorts on a small boy with pant legs three times the girth of his legs sent me into midcentury flashbacks of mid-century childhood.

The setting had to represent several locations in the town, including the main street, the interior of a house, a jail, a courtroom, all with only one major change that was achieved flawlessly. Its look was raw, dry, well cut wood that played all of its roles well.

Lighting was clear both in function and artistic presentation. Cues brought us immediately into the mood of the scene before the action erupted in place. There were sounds that brought us into and out of scenes and one well-recorded gunshot.

The ensemble was well-cast and very well suited to their roles. Two regulars whom I have seen multiple times in casts outdid themselves, seeming to find in their roles a believable solidity and a deep emotional connection: Ian Lane as Heck Tate and Stephanie Wood as the highly opinionated Stephanie Crawford. Additionally, the child ensemble of Elani Roza Yanex, Grayson Lewis, Mathias Glick as respectively the Finch children and neighbor Dill work well together and share a very comical set of moments with Ashlee James as Calpurnia.

Others shine as brightly: Andrea Kahane as Maudie, the narrator and the Finches neighbor, is compassionate and carries the stage well until she turns it over to the next scene.

Anthony Williams as Tom Robinson has a quiet dignity in the face of an outrageous accusation of rape. He has tried to help everyone he has contact with in the town, and received unfounded resentment in return. Frequent uses of the “N” word in the dialog to describe him relegate him to a stereotype which the town seems eager to reinforce but Atticus treats him as an individual and allow us to see him for what he is.

Tom is accused by Mayella Ewell (Sarah Stewart) and her father Bob (William Johnson), both of whom remain human in their characters which express personified prejudice. Their entitled rage shows in their determination to use a broken system to exact revenge on the world.

The authors send in a bit of a McGuffin character in Boo Radley (David Landrum). He is set up as a possible danger to the world around him but ends up only fulfilling the needs of the moment. His action ends the melodramatic climax to the show, and leads us into the tragic final moments.

Each character in the town has their moment to shine, for good or for ill. The authors use the character of Walter Cunningham as the embodiment of the town and its tendency to overreact. C.C. Gallagher plays this well. Characterizations which are that briefly seen come quickly into focus and then fade into the background, then gradually weave themselves into the tapestry of a small town life. That we will only see fully once the final denouement has been revealed and the play goes from hope to tragedy. As I mentioned before, the audience is treated as the jury, witnessing the tiny moments, clues, and cues that create the non-mystery. The jury is left to judge itself on evidence we’ve presented not only by lawyers and witnesses at the trial but in the actions of everyone we’ve experienced. But will the jury of record agree with the jury in the audience for the play?

In the end, this is a show about Atticus Finch, a local attorney who has the problem not only of keeping his client out of prison for what is shown to be a trumped-up charge, but keeping him alive until the trial begins. He proves at the beginning that he is unafraid to take justified action in the face of danger to others, shooting a rabid dog.

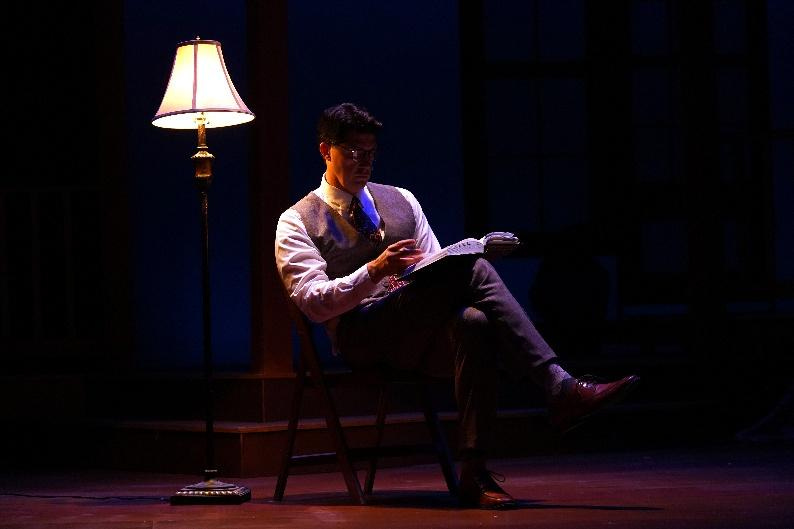

He also is unafraid to face down a mob and remind them that they are human beings with troubles of their own. Tug Coker does not simply portray a character, he embodies both Atticus’s presence and spirit with a quiet intensity. He is the quiet center of a hurricane of emotions, attempting to shield the innocent from dangers with reason and humanity.

The show has an amazing restraint. It could descend into preachiness, since it so strongly establishes Atticus’s moral high ground. It could turn into pure legal melodrama, but the script and the strong production keep pulling us back from easy decisions that reinforce our own prejudices. It is built as a case not against a person but against a set of social interactions. It shows conflict, but is not physically violent. In fact, both the violence and the aftermath of violence most often happen offstage. What we see and hear is the testimony of the survivors, and the play ascends from melodrama to tragedy in a most beautiful way.

Normally I close reviews with a recommendation to “see it” or offer caveats for potential audience members. I have no reservations but only enthusiasm for you to see this show. To Kill a Mockingbird is not to be missed.

Dennis Wemm is a retired professor of theatre and communication, having taught and led both departments at Glenville State College for 34 years. In his off time he was president and sometimes Executive Director of the West Virginia Theatre Conference, secretary and president of the Southeastern Theatre Conference, and generally enjoyed a life in theatre.

(TLDR) Dramaturgical notes for the play:

To Kill a Mockingbird has had a long and storied history as a stage production. Harper Lee’s novel was published in 1960, the Horton Foote-written movie appeared in 1962, and the initial stage adaptation was written for Dramatic Publishing Co. (a play publisher that specialized in amateur theatre group scripts) by the company’s owner (1969-1970). All three were hits in their respective spheres.

Other adaptations followed, some sanctioned by Lee and later her estate while some were not. Sergel rewrote his adaptation in 1990, changing some staging ideas-most notably the identity of the narrator.

Riverside’s production uses the 1970 version, most notably using the sympathetic narration for the play being done by Mrs. Maudie, who in the novel is an advisor and mother figure to Scout and Jem. Later productions used an adult version of Scout as a narrator. In 2019 a new award-winning script, adapted by Adam Sorkin, was produced on Broadway and performed to packed houses until closed by the pandemic lockdown in 2020. It reopened in 2021 and was closed by its lead producer in 2022. The show has since been touring across the country in the Sorkin version which was recognized for all highly commercial productions in highly populated areas.

Support the Advance with an Annual Subscription or Make a One-time Donation

The Advance has developed a reputation for fearless journalism. Our team delivers well-researched local stories, detailed analysis of the events that are shaping our region, and a forum for robust, informed discussion about current issues.

We need your help to do this work, and there are two ways you can support this work.

Sign up for annual, renewable subscription.

Make a one-time donation of any amount.

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit the link that follows.

This article is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. It can be distributed for noncommercial purposes and must include the following: “Published with permission by FXBG Advance.”