"All the Presents Were Bought, Wrapped, and Under the Tree, and I Wasn't There"

Local women share their experiences of being incarcerated over the holidays.

By Adele Uphaus

MANAGING EDITOR AND CORRESPONDENT

Email Adele

This Christmas will be extra meaningful for Tonia Garnett.

Not because there’s a special gift or trip planned—but simply because she’ll be home, with her family.

“This Christmas, for me, is going to be such a joyous moment,” said Garnett, who now works as peer support specialist at FailSafe-ERA, the Fredericksburg area nonprofit that supports justice-involved individuals and their families.

Garnett spent last Christmas in the Rappahannock Regional Jail.

She was arrested a week before Christmas on a charge of violating her probation.

“We tried to get me bond and I had such high hopes,” Garnett told the Advance. “I walked out of the court room feeling so low. When you walk back into the pod, everyone’s eyes are asking, ‘Did you get bond?’ And you break down and cry.”

“All the Christmas presents were bought, wrapped, and under the tree, and I wasn’t there.”

Christmas is a special time for families of all kinds, but it’s a time of heightened wonder and excitement for children in particular—and at the core of the religious holiday is the celebration of a baby and his mother. So it can be extra painful for mothers, or those who mother, to be incarcerated at this time of year.

More than 150 local women will spend this holiday inside the Rappahannock Regional Jail. As of December 16, the female population at the jail was 166, superintendent Kevin Hudson said. Some of them are serving sentences—many for nonviolent crimes such as possession of drugs or violation of probation—but some have not yet been charged or are awaiting bond hearings.

And for many of them, the pain of being separated from families at this time of year is compounded by feelings of guilt.

Garnett and her husband have been raising their grandson since the death of their daughter in a car accident in 2021. For Garnett, the most special time with her grandson is when she lies in bed with him as he’s falling asleep and everything he’s been thinking about during the day comes pouring out.

He was six years old when she went into the jail last year and “I would sit in my jail cell at night and tears would well up in my eyes as I thought about him laying in the bed and not having me there,” she shared.

“Guilt and shame would rise up inside me because I was not wrongfully incarcerated. I committed a crime,” she continued. “It’s an incredible burden you feel as an inmate—you know that the harm and the hurt and the pain you cause a child is totally all your fault. And though you are not the decisions that you make—I’m not a bad person, but I made a bad decision.”

Samantha Stoudt, a client of FailSafe who spent nine months—including the Christmas and Easter holidays—in Rappahannock Regional Jail, also described her feelings of guilt about being separated from her children.

Her two children were separated when she was arrested for possession of drugs in 2017—her first time ever being in trouble with the law.

“That was the hardest,” she said. “I was able to have my mom bring my oldest son to come see me while I was incarcerated around the holidays, but my [younger] son’s father didn’t want anything to do with me during that time. I would write letters and they would send me pictures here and there, but other than that, they didn’t want me to be around, which hurt me the most. Especially being clean and sober, you realize the mistakes you made.”

Studies have found that many, if not most, women who are imprisoned have already experienced some kind of trauma. According to a 2024 report by the Women and Justice Project—which incorporated both state and national studies—between 70- and 80% of incarcerated women are survivors of intimate partner violence; 60% experienced caregiver violence as children; 86% have experienced sexual violence during their lifetime; and 53% have a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Overwhelmingly, women enter prison with significant mental health care needs and require a high-level of care that is largely reflective of the nearly ubiquitous nature of trauma, psychological distress, and addiction,” a 2025 article in the journal Social Sciences states. “The level of care needed, in response to the varied and complicated diagnostic profile of incarcerated women (e.g., ADHD, psychosis, trauma), as well as the number of critical incidents stemming from symptoms, reflects the need for more clinical staff to expand reach along with training in a wide range of modalities.”

Many women, Garnett said, are “retraumatized by incarceration,” especially when there is a shortage of staff that leads to lockdowns during which people are confined to their cells, and when communication with loved ones on the outside can be so costly as to be prohibitive.

Stoudt said she had a miscarriage at 26 weeks while incarcerated. The medical care she had to receive swallowed all the money that family members put on her account, so she was not able to afford video visits.

Under these lonely circumstances, the smallest allowances make the biggest difference, the women said.

“My brother had a probation violation and he was incarcerated during Christmas and New Years in Rappahannock Regional Jail the same time as me,” Stoudt said. “We were not allowed to see each other or talk, but we could write each other. I still have those letters.”

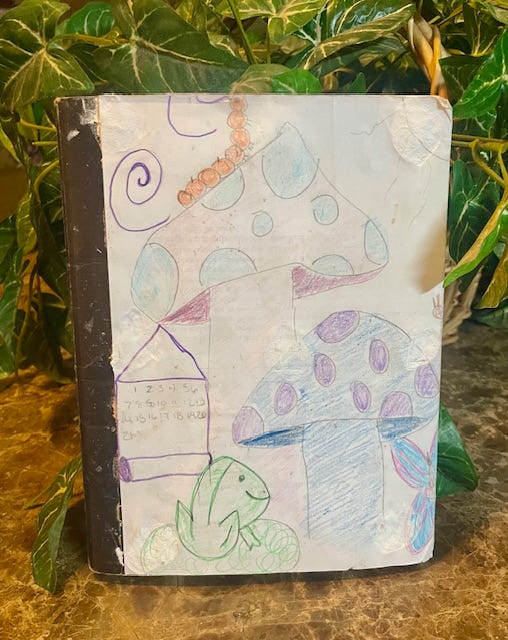

Garnett said she and the other women in her cell and in the pod would make each other cards using notepaper and colored pencils they bought from the commissary.

“We would draw them or pay someone else a commissary item to draw one,” she said. “Those that could afford commissary would wrap up little gifts like a bag of chips, using newspaper or whatever paper we had as wrapping paper.”

Garnett said she made a Christmas card for one of the female correctional officers during her first holiday in Rappahannock Regional Jail in 2022. She recently re-connected with the woman via social media to wish her a happy Thanksgiving.

“She said, ‘I still have your card,’” Garnett recalled. “Hearing that was validating. There are people in there who don’t dehumanize you, and who do relate to the fact that you are a person who made a decision to make something for them.”

However, she said there was a rule against passing items from one person to another.

“If the officers see you pass something, they’re supposed to come and take it,” she said. “Most officers do not, but there was one occasion where someone did take a card [I was trying to pass to another woman]. I asked for it to be put with [her] personal property so when [she was] released, it would still be there—but they said, ‘No, policy is we have to throw it in the trash.’ And they did. And it was heartbreaking.”

“When that happens, you feel so dehumanized,” Garnett said.

Thanks to nonprofit groups, people incarcerated at the jail do receive a small gift on Christmas Day, the women said—a care package containing socks, a t-shirt, a tube of toothpaste, and a toothbrush.

“That was a positive to wake up to,” Stoudt said. “And we did get a nice Christmas dinner—instead of the jail food, we got turkey or something that was different.”

Garnett said the women in her pod came together to create a special meal on Christmas Day, something they called “a flip.” It was made up of sausage meat, Ramen noodles, cheese puffs, and diced pickles, mixed up and microwaved until firm and then topped with “honey mustard”—a mix of mayonnaise, mustard, and a sweetener packet.

“Then you flip it over like a casserole or a giant sandwich and divide it among the ones who contributed… plus a few who had nothing to offer,” Garnett wrote. And let me tell you, in a place where you feel less than human… a meal made with your own hands and shared with others can make you feel seen.”

Longterm, however, both Garnett and Stoudt said that what got them through their time in Rappahannock Regional Jail was participating in the jail ministry program and the groups facilitated by outside groups such as FailSafe and Christian Brothers Transition Program.

“I took the initiative and signed up for every class,” Stoudt said. “I was getting pulled out for a group every day or at least twice a week, so I didn’t get out of the pod, but at least I got out of my cell.”

Garnett said that during her incarceration last year, she was finally able to identify the cycle of self-sabotage she’d been caught in.

“Anything I had built good in my life, I tore it down,” she said. “It wasn’t until this last incarceration that I had that pivotal moment where I was able to sit through the programs and classes that supported me in getting a grip on identifying not just the trauma that had occurred in my life, but the decisions I made after those traumas.”

This Christmas, Garnett and her grandson do have one new activity planned.

“We’re participating in [FailSafe’s] Holiday Shoppe where we’re providing presents for children [impacted by incarceration],” she said.

Garnett’s holiday wish for those who are still on the inside is that they not give up on themselves and that they are allowed opportunities, however small, for connection.

“Because at the end of the day, the majority are coming home, and the question is, are they going to come home stronger or more traumatized?” she said. “And what I want—my hope for them—is to come home stronger.”

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit the link that follows.

Support Award-winning, Locally Focused Journalism

The FXBG Advance cuts through the talking points to deliver both incisive and informative news about the issues, people, and organizations that daily affect your life. And we do it in a multi-partisan format that has no equal in this region. Over the past year, our reporting was:

First to break the story of Stafford Board of Supervisors dismissing a citizen library board member for “misconduct,” without informing the citizen or explaining what the person allegedly did wrong.

First to explain falling water levels in the Rappahannock Canal.

First to detail controversial traffic numbers submitted by Stafford staff on the Buc-ee’s project

Our media group also offers the most-extensive election coverage in the region and regular columnists like:

And our newsroom is led by the most-experienced and most-awarded journalists in the region — Adele Uphaus (Managing Editor and multiple VPA award-winner) and Martin Davis (Editor-in-Chief, 2022 Opinion Writer of the Year in Virginia and more than 25 years reporting from around the country and the world).

For just $8 a month, you can help support top-flight journalism that puts people over policies.

Your contributions 100% support our journalists.

Help us as we continue to grow!

This article is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. It can be distributed for noncommercial purposes and must include the following: “Published with permission by FXBG Advance.”

Thanks for writing this, Adele.