ANALYSIS: Teachers Are Key to Success on State's New Accreditation Standard

The new accountability standards taking effect in 2025, and the Virginia Literacy Act, have upset school districts' apple carts. Empowering teachers is key to navigating the new environment.

By Martin Davis

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Email Martin

It is fair to say that Virginia’s new accountability system has local school districts on edge as they prepare for its 2024-2025 rollout.

And for good reason.

While it’s not clear what the consequences will be for failing to make the grade, some fear that the state will use failing data to take control of schools.

And in our region, numerous schools have a great deal of work to do.

As the Advance reported in October, only one school in the Fredericksburg school system, Lafayette Elementary, was fully accredited under the previous accreditation system. The other three schools were “accredited with conditions.”

In Spotsylvania, 15 — nearly half — of the district’s schools would be identified as “off track” or “needing intensive support” under the Virginia Department of Education’s new accountability framework, according to a press release from the district.

There is little doubt that the new accountability system is difficult to fully understand, and that there remain ongoing issues. Nonetheless, this new system will be a political reality beginning next year, so figuring out how to navigate these waters is critical to schools’ success.

Breaking Down the Approach

In Southwest Virginia, the Comprehensive Instructional Program (CIP) — a consortium of more than 70 mostly small school districts in Virginia — has taken the same approach to this problem as it has countless others. Empowering districts and teachers with actionable data and information.

“Knowledge is power” said Michelle Greene, who is the principal at Riverlawn Elementary School in Pulaski County. “Helping staff understand the accountability system so they have more buy-in … empower[s] them to … reach that goal.”

The “knowledge” that Greene references goes beyond what some districts in the state are offering their leaders and teachers. Having previously worked in a non-CIP district, Greene knows that there are schools in Virginia that are not getting a “deeper dive into the accountability system that we get when we attend CIP meetings.”

While the Virginia Department of Education has provided all the necessary data from last year to help districts calculate what those scores would have looked like under the new accreditation system, the CIP program wanted to simplify that information so it would be easier for administrators and teachers to use and understand, said CIP Director Matt Hurt.

Working with his team, Hurt put together a training that included both PowerPoint presentations and, most important, a simplified Excel spreadsheet that allowed those attending a leadership academy meeting for Region 7 schools in early December to easily calculate how their most-recent SOL data would have scored under the new accountability system.

This simplified spreadsheet lets people insert their own data, thereby letting them better understand how adjustments in one area affect their school.

The transmission of that information did not stop with attendees of the leadership academy meeting, however.

Both Greene and Jennifer McGee, principal of Graham Middle in Tazewell County, report that the training and the spreadsheets were passed on to individual teachers. Some may see this as information more appropriately kept at the central office level, but Greene and McGee disagree.

By sharing the calculations, McGee told the Advance, “teachers better understand how it affects us all when a student scores advance, pass, or fail.”

“We look at data at multiple levels,” Greene continues, “school, class, student, etc.”

This “broken down look” at the data, says Greene, is what is empowering schools and teachers in Pulaski County to feel better prepared for the new accreditation world coming next school year.

But simply sharing the data alone isn’t enough to affect change. As important as the numbers are, it’s the supports that districts provide their teachers, and the ways that that support is delivered that’s having the greatest impact.

Retaining Individuality in a Sea of Data

There’s a saying that Hurt likes to poke fun at when talking about the use of data in the education environment.

“The beatings will continue,” he says with a sly laugh, “until morale improves.”

Anyone who works a job where data are a key part of their evaluations will understand the joke. Talking about data can get to feel like punishment — “Get the numbers up,” the boss says, but he or she offers no real road map for precisely how to accomplish that goal.

The CIP program turns that paradigm on its head.

Data is not the whip driving the horse forward, but rather the horse itself that powers the engine of teacher creativity.

While allowing teachers to directly manipulate data allows them to better understand how their students’ performance affects their school writ large, that doesn’t help them understand how to pull those numbers up.

That happens when administrators deliver the types of support that allow teachers to reach into their creative toolboxes to figure out what will work best for their classes.

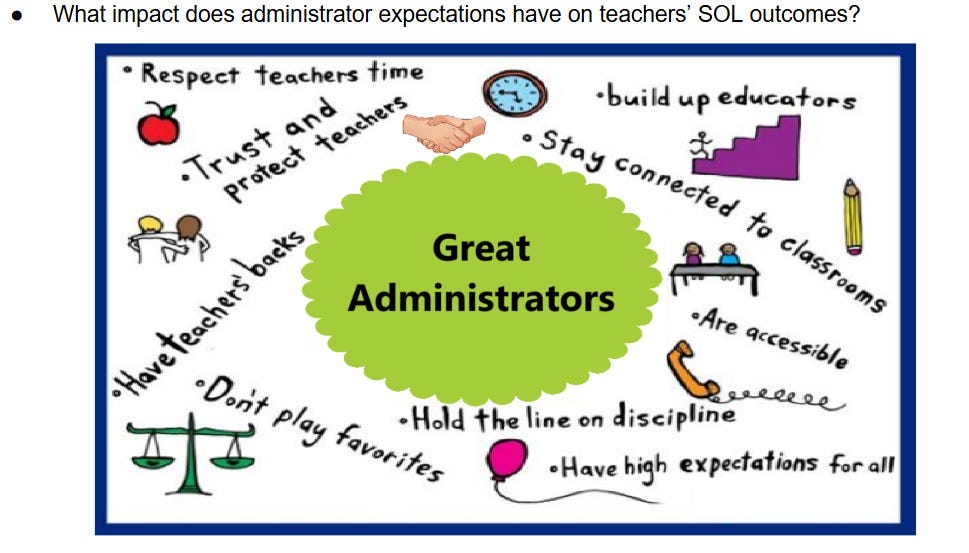

In the training CIP delivered to Region 7 leaders, that point was made clear in the following slide from the PowerPoint presentation.

Notably absent from this list is regular data meetings, or heaping mandates from on high that add to already-overburdened teachers’ days.

Rather, the focus is on trust, protecting teachers, freeing up their time, and creating schools where students understand the rules and are not allowed to disrupt classroom learning or the day-to-day activities of the school itself.

In our discussions with Greene and McGee, this balancing act between data and teacher support is key to how the schools are addressing the requirements of the new Virginia Literacy Act.

What has proven challenging for many teachers is that the VLA doesn’t simply readjust the standards around teaching, but it dictates the curriculum.

“Whenever you have a canned program you have to use,” says Greene, you “have to find that balance” between what’s required and teacher creativity. Teachers have to add their own flair to it.”

That means administrators have to find the positives in the approach and pursue those. “How we sell that program as administrators is important,” she said.

McGee reports that the hardest challenge for Tazewell County with the new VLA is that the groups students are broken into are so small that “everyone has to teach it.”

That’s a problem, says Greene, because “teacher prep programs aren’t giving students exactly what they need to teach reading.” This means requiring teachers to start teaching something they don’t know, which makes them uncomfortable.

Tazewell County’s efforts to this point in the year have been mostly good, says McGee. “We are seeing some pretty good outcomes out of the first benchmarks.”

“With our English Learners community,” she continues, “the results have been mixed.” Here, taking a deep dive into testing data is allowing administrators and teachers to understand what is and isn’t working, and make the necessary adjustments.

Parents, Voters Have a Responsibility, Too

The United States has been driven by outcomes-based, high-stakes testing since 2001. The original goal of No Child Left Behind was that by 2014 every child — 100% of them — would perform at grade level on state testing scores.

That mindset set schools up for failure.

Andrew Ho of Harvard University told NPR in 2014:

Leaving no child behind is the right rhetorical goal. It generally resonates with educators, students, teachers, administrators, and the public. We don't want to leave a child behind, and the standard we want them to achieve should be high.

However, he continued:

I think it's safe to say, and we anticipated this early on, that policymakers erred. They turned an aspirational goal that inspires support, into a target for accountability, meant for consequences.

Under Gov. Glenn Youngkin, the public school system has been targeted and blamed for SOL results, sometimes using deceptive data; teachers have been targeted with both the short-lived tip line for parents to out those they suspected of teaching “dangerous ideas” and the ire of “parents’ rights” groups; and curriculum has been politicized over issues such as the roles of race and slavery in U.S. history.

The consequences are evident at school board meetings across the commonwealth, where parents and voters have followed the governor’s misuse of data to claim the public schools writ large are failing, and in the governor’s never-ceasing demand to improve scores with no real explanation for how that is to occur. Youngkin’s answer — and the answer of many parents and voters — is too often, “more tests!”

The new accreditation standards will serve the commonwealth no better than the old accreditation standards if every test season the governor and parents’ groups continue to use the data to perpetually paint a picture of failing schools, but then do little to understand why the scores are what they are and work to address the problems.

To better understand Virginia’s new accreditation system, please read the presentation on the new system CIP made to Region 7 leaders.

Elementary and Middle School Accreditation Standards

High School Accreditation Standards

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit the link that follows.

Support Award-winning, Locally Focused Journalism

The FXBG Advance cuts through the talking points to deliver both incisive and informative news about the issues, people, and organizations that daily affect your life. And we do it in a multi-partisan format that has no equal in this region. Over the past year, our reporting was:

First to break the story of Stafford Board of Supervisors dismissing a citizen library board member for “misconduct,” without informing the citizen or explaining what the person allegedly did wrong.

First to explain falling water levels in the Rappahannock Canal.

First to detail controversial traffic numbers submitted by Stafford staff on the Buc-ee’s project

Our media group also offers the most-extensive election coverage in the region and regular columnists like:

And our newsroom is led by the most-experienced and most-awarded journalists in the region — Adele Uphaus (Managing Editor and multiple VPA award-winner) and Martin Davis (Editor-in-Chief, 2022 Opinion Writer of the Year in Virginia and more than 25 years reporting from around the country and the world).

For just $8 a month, you can help support top-flight journalism that puts people over policies.

Your contributions 100% support our journalists.

Help us as we continue to grow!

The question left unasked is: are the teachers successfully teaching the children reading, math, science, and civics? For many, the answer is, no. The excuses are innumerable, but what are they teaching? Who is teaching the teachers and what?