DIGITAL INSIGHTS: How Much Data Is There?

It's a long way from the Middle Ages to now, but looking back 1,000 years can bring some perspective on what is happening with information, its growth, and its storage and dissemination.

By Martin Davis

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Email Martin

In writing this final Digital Insights column for 2025, I wanted to reflect on what the column has accomplished this year. Instead, I found myself thinking more about the questions that people have raised about data centers: Why are data centers so large? Why do we need so many of them? And why are we building them so rapidly?

The questions are revealing, as they reveal that people’s unease isn’t necessarily with data centers themselves but rather the scale at which they are growing. That concern in understandable. We have not seen change on this scale in the country, arguably, since the automobile transformed the way people travel and the where we live.

That insight led me to an old corner of my professional past — the monastic libraries of medieval England.

Prior to becoming a professional journalist some 25-plus years ago, I was training to be a scholar of medieval history. My research interests were abbots, their education, and how monastic learning spread across England and France in the 11th and 12th centuries. As it turns out, libraries were the tool for tracing that history.

Medieval libraries were relatively small, most having no more than 100 to 200 books. Knowing which house an abbot was trained in, it was relatively easy to read in a year or two most everything a given abbot read in his entire life.

That reality hit me early in my graduate studies, when within a year I had effectively read all the extent works that Lanfranc, the first Norman abbot of Canterbury, had read in his life.

What has this to do with data centers?

It provides a starting point for establishing a scale to better understand how limited information was then, and how expansive information is today.

It also leads to an interesting parallel — the relationship between the repository of medieval monastic learning, the monastic libraries of the Middle Ages, and the repositories of learning today. Data centers.

How Many Bytes Did the Average Abbot Read?

For most of human history, the amount of information available to any given human was relatively small. Consider 11th century England.

An abbot trained in a medium-sized library during that period would have read about 40,000 pages of text in his lifetime. How do we know? Because a medium-sized monastic library contained only about 100 books. Based on my experience reading significant numbers of books that were stored in these libraries, it’s fair to estimate that the average length of these books were about 400 pages.

Now, imagine that this monk didn’t read the book on vellum, but on a Nook. How much storage space would be required to hold 40,000 pages of text?

The average modern 400-page digitized book with no images consumes between 1 and 1.5 megabytes of data. So our medieval abbot with a nook would need about 150 Mbs of storage space to hold all the knowledge at his disposal in his 11th century home monastery.

Not a problem, as the Nook GlowLight 4 has 32 Gigabytes of storage space. In other words, the abbot could store the equivalent of an addition 218 medieval libraries — each containing 100 books — on his Nook.

So How Much Data Is Available Today?

The world of the 11th century abbot, when looked at in terms of available knowledge, looks rather limited by today’s standards. It’s also important to know, too, that the amount of available information didn’t grow all that rapidly.

Some 600 years later, Thomas Jefferson had roughly 6,500 books in his personal library. Using the same estimates — each book has an average of 400 pages and would require about 1.5 megabytes to store digitally — one could fit three libraries the size of Thomas Jefferson’s on one Nook.

While considerably more than our medieval abbot had at his disposal, it was still possible in Jefferson’s day to read every book in that library in one’s lifetime.

What about today?

Well, let’s just say the world has changed.

Indeed, it is truly difficult to grasp just how much knowledge can be dialed up at any moment by a human being any place in the world there’s an internet connection.

Difficult, but not impossible. Starting at the macro level, the total amount of data in the world in 2024 was estimated to be 149 zettabytes.

To begin to comprehend that number, we need to back up and look at how data is measured.

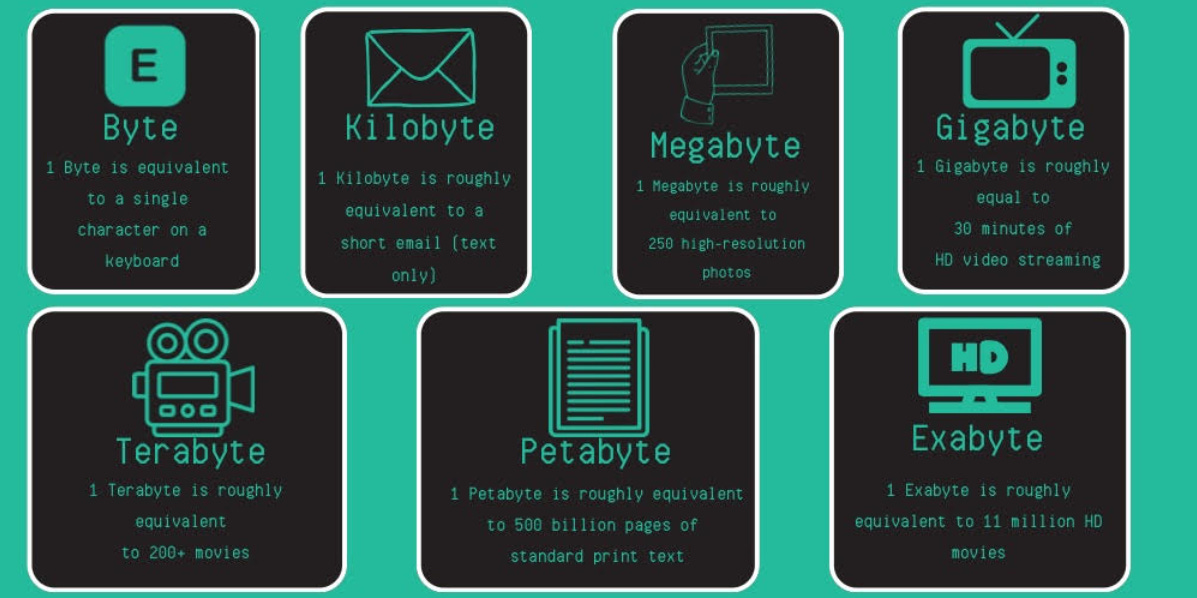

The base data unit is the byte, which is roughly equivalent to one character on a keyboard.

Each step up represents an exponential leap. So, a kilobyte is not 1,000 bytes, but 210 power, or 1,024 bytes. And from there, the numbers explode. A megabyte is 10242 power, or 1,048,576 bytes. A gigabyte is 10243 power, or 1,073,741,824 bytes.

Now, a reader warning. I’m not a mathematician — I’m a writer. So I’m going to quote from GeeksforGeeks.org to explain the magnitude of each step up the ladder.

By the time we reach a gigabyte (i.e. 10243 bytes), the difference between the base two and base ten amounts is almost 71 megabytes.

And we are nowhere close to reaching a zettabyte.

The next step up from a gigabyte is a terabyte, which is enough space to hold more than 200 movies.

From there, we move to a Petabyte, which holds 500 Billion pages of standard text print. Next is the exabyte, which can hold 11 million HD movies.

Only then do we reach the zettabyte, which is equivalent to 1 Trillion (with a “T”) gigabytes.

Visualizing a zettabyte is difficult enough, much less how much data 149 zettabytes represents.

And this number is not sitting still. Every day, there are an additional 402.74 million terabytes of data generated.

A medieval library could hold a significant piece of the written knowledge in the 11th century, it couldn’t begin to hold the amount of information available today.

Enter data centers.

The amount of data that any data center processes daily varies based on the type of information it handles. The numbers can range from gigabytes to petabytes.

At these scales, it becomes a bit easier to understand why the demand for data centers is growing as rapidly as it is.

A Long Way from Cluny

The Cluny monastery in France held one of the larger monastic libraries in medieval Europe. In many ways, it was the center of the monastic world and as such would grow rapidly between the 11th and 14th centuries, spreading over all of Europe. And with it, traveled the knowledge stored in its libraries.

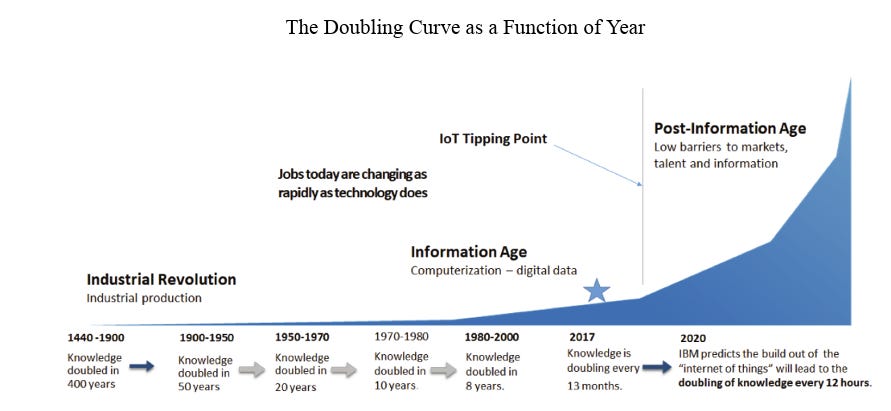

While Cluny grew, however, new knowledge grew very little. In fact, it has only been over the course of the past 15 years that knowledge — measured in terms of information available — began to grow exponentially.

In the middle ages, knowledge doubled roughly every 400 years. By 1900, it was doubling every 50 years.

Now, it is doubling every 12 hours, according to some experts.

That’s a scale which a medieval monk couldn’t possibly grasp. The truth is, we today are also struggling to grapple with that scale of growth.

It requires rethinking our relationship with information, as well as the way that information is stored and distributed.

In 2026, this column will have more to say about how today’s data flow is affecting our relationship with information.

For now, it helps to visualize this growth in information by looking at data centers in the same way an abbot would look at a medieval chapter library. The great repositories of knowledge and information. That’s what it takes to hold it all.

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit the link that follows.

Support Award-winning, Locally Focused Journalism

The FXBG Advance cuts through the talking points to deliver both incisive and informative news about the issues, people, and organizations that daily affect your life. And we do it in a multi-partisan format that has no equal in this region. Over the past year, our reporting was:

First to break the story of Stafford Board of Supervisors dismissing a citizen library board member for “misconduct,” without informing the citizen or explaining what the person allegedly did wrong.

First to explain falling water levels in the Rappahannock Canal.

First to detail controversial traffic numbers submitted by Stafford staff on the Buc-ee’s project

Our media group also offers the most-extensive election coverage in the region and regular columnists like:

And our newsroom is led by the most-experienced and most-awarded journalists in the region — Adele Uphaus (Managing Editor and multiple VPA award-winner) and Martin Davis (Editor-in-Chief, 2022 Opinion Writer of the Year in Virginia and more than 25 years reporting from around the country and the world).

For just $8 a month, you can help support top-flight journalism that puts people over policies.

Your contributions 100% support our journalists.

Help us as we continue to grow!

This article is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. It can be distributed for noncommercial purposes and must include the following: “Published with permission by FXBG Advance.”

A good primer. Where are we as it relates to disposing of data - is technology outpacing policy? I hope all my personal data is being eliminated as required by law.