DIGITAL INSIGHTS: Will AI Become a Net Plus for the Environment?

The question is based on a longer running human debate -- does scarcity lead to devastation, or does it drive innovation?

By Martin Davis

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Email Martin

Digital Insights appears on Thursdays and explores the role of data centers in our region. These columns will focus on four areas: tracking the development of data centers in our area, exploring projected and actual tax revenue trends, explaining what data centers are and how they affect our daily lives, and reporting on research and emerging trends in the industry. These columns are made possible, in part, by a grant from Stack Infrastructure.

The future projections about energy use driven by artificial Intelligence (AI) are cause for concern. “In the United States,” according to a report issued earlier this year by the International Energy Agency, “power consumption by data centres is on course to account for almost half of the growth in electricity demand between now and 2030.”

These numbers are intimidating for several reasons — the speed with which this change has come, and the size of growth projected in a compressed timeframe. And they are frequently pointed to as evidence that our environment is on a crash course with environmental degradation.

Though this particular problem is new to the human experience, it’s not the first time that humans have faced equally significant upheavals and wrestled with whether it would cause devastation or prosperity.

A look back is instructive for how we debate and understand the challenge before us.

The Industrial Revolution and Fear of Starvation

At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the early 18th century, the concern wasn’t energy use, but food.

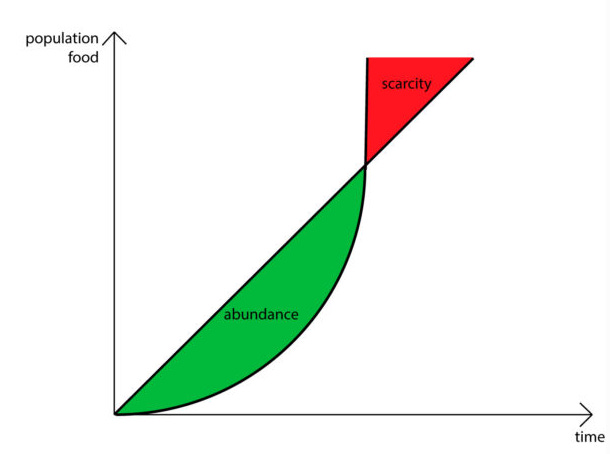

Human population growth from the beginning of the Roman Empire to the start of the Industrial Revolution had been modest. In the year 1 A.D., the total human population was about 170 million people. It would take to roughly 800 A.D. for the population to reach 200 million. By 1100 A.D., as Europe warmed, the population reached 300 million. It grew to 400 million around 1450 A.D.

In short, it took a little less than 1,500 years for the population to double.

Between 1700 and 1800 A.D., however — a period of just 100 years — the human population nearly doubled. It grew from 590 million to 1 billion people.

Thomas Malthus was born in 1766, when population was growing at a rate never before seen in world history. Even with the agricultural revolutions being brought by the Industrial Revolution, he felt that farmers would not be able to meet the growing demand for food, leading to mass starvation and a dying off of the human population.

His theory continues to have sway in public discourse, through books like The Population Bomb (1968). Some, like Thomas Robertson who wrote The Malthusian Moment, have tied the environmental movement to Malthusian concerns about scarcity.

Fortunately, to date, Malthus has been proven incorrect. But why have his ideas not become reality?

The answer, it turns out, has to do with people’s ability to solve technological issues.

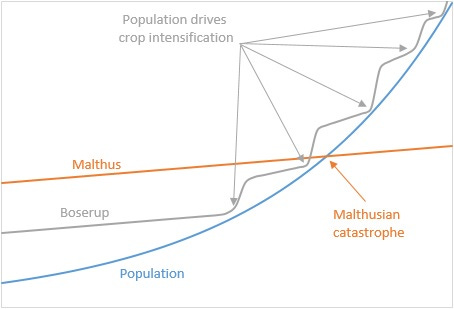

Ester Boserup was a Danish economist who in 1965 wrote The Conditions of Agricultural Growth, which flipped Malthus’ idea, “arguing that increases in population (or land) pressure trigger the development or use of technologies and management strategies to increase production commensurate with demand.” (For a fuller treatment of Boserup, see this PNAS essay.)

Whereas Malthus focused on scarcity, Boserup focused on the human capacity for adaptation, change, and innovation.

Malthus, Boserup, and AI?

Against this backdrop, let’s return to the original question: Are the energy and water challenges we are facing owing to AI putting our environment on a course to irreparable degradation?

That’s the question that two faculty members at the University of Mary Washington debated in an event put on by the UMW Center for AI and the Liberal Arts early in September.

Arguing that AI would have a net negative effect on the environment over the next decade was Kaitlyn Haynal. Arguing AI would have a net positive impact was Mike Reno.

Haynal based her argument on four points:

AI is built on extractive and colonial supply chains, and it depends on rare-earth metals that are projected to run out.

AI’s production and use are environmentally unsustainable — especially generative models.

AI accelerates fossil fuel expansion.

AI is shaped by ownership and ideology — in other words, it’s created by companies to maximize profit, with no concern for the people or planet.

The argument has Malthusian overtones — notably, AI’s development will ultimately lead to the decimation of the very resources AI needs to thrive and grow.

Reno’s argument, by contrast, has overtones of Boserup. He takes Haynal’s argument point-by-point:

On AI depending on colonialism and extractive minerals, he argues, in part, that there actually are plenty of “rare-earth” minerals, they’re just hard to extract.

On AI’s accelerating fossil fuel production, he argues that the development of renewable energies far outstrips fossil fuels. Further, the administration of AI to manufacturing has already reduced energy consumption.

On AI being based on a reckless “tech-bro”-type optimism, he argues this is unrelated to addressing the resolution.

Finally, on the argument that AI is unsustainable, he states that AI is already reducing fossil energy use and increasing the efficiency of renewables. Further, concerning grid management, AI is critical to balancing the increasing energy needs and the growing renewable energy sources that feed those needs. In fact, without AI, such balancing would not be possible. This is why AI and renewables are “the new power coupled.”

Here, Boserup’s influence is clear. The pressure point — energy use to drive AI — is leading to innovations that will keep us from facing the catastrophic results should energy supplies fail.

The forum itself is more detailed than what is outlined here, but worth the time to get a better sense of the issues and opportunities associated with AI development.

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit the link that follows.

Support Award-winning, Locally Focused Journalism

The FXBG Advance cuts through the talking points to deliver both incisive and informative news about the issues, people, and organizations that daily affect your life. And we do it in a multi-partisan format that has no equal in this region. Over the past year, our reporting was:

First to break the story of Stafford Board of Supervisors dismissing a citizen library board member for “misconduct,” without informing the citizen or explaining what the person allegedly did wrong.

First to explain falling water levels in the Rappahannock Canal.

First to detail controversial traffic numbers submitted by Stafford staff on the Buc-ee’s project

Our media group also offers the most-extensive election coverage in the region and regular columnists like:

And our newsroom is led by the most-experienced and most-awarded journalists in the region — Adele Uphaus (Managing Editor and multiple VPA award-winner) and Martin Davis (Editor-in-Chief, 2022 Opinion Writer of the Year in Virginia and more than 25 years reporting from around the country and the world).

For just $8 a month, you can help support top-flight journalism that puts people over policies.

Your contributions 100% support our journalists.

Help us as we continue to grow!

This article is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. It can be distributed for noncommercial purposes and must include the following: “Published with permission by FXBG Advance.”

Seriously, Dr. Philosopher? The spread of AI and the proliferation of data centers is going to have a net positive impact on the environment? What about the construction of new generating facilities and the transmission and distribution infrastructure to get the power to the data centers? Where is the water going to come from for cooling both the data centers and the power generation plants? Google (yes, I know, AI will kick in to assist in the search) how Dominion Energy is planning on meeting the needs of these monster consumers and what the corresponding rate increases will do to residential users. Environmental degradation ALWAYS occurs where there are extractive activities (raw materials to build and operate all of the above) as well as bringing along direct costs to consumers and the related negative externalities to the environment.

And thanks for ignoring the environmental degradation (mostly noise) in the communities that "host" the data centers.

Production of rare earth: China refines 90% of them. No problem there.

The environmental concerns are only part of the downside to AI. For a pretty clear picture of the cultural, economic, social side see The Daily Show interview by Jon Stewart of Tristan Harris, the co-founder of the Center for Humane Technology on Oct 6. This should be required viewing for all philosophy professors and students.

Lastly, read How the World Really Works by Vaclav Smil to get a better feel for the pickle we are in and how there is no near-term off-ramp, notwithstanding the considered opinions of those who believe technology will save us like it always has.

Thank you to 'Advance' for making sure to include who is funding this Thursday DATA CENTER column made possible, in part, by a grant from Stack Infrastructure.

Stack Infrastructure is the DATA CENTER developer for the CVA Project out near Wegman's and the Fred Nats ballpark. Kevin Hughes, with Stack Infrastructure, sits on the Fredericksburg EDA Economic Development Authority.

Residents in Prince William Co were successful in knocking Stack Infrastructure, Kevin Hughes off their DATA CENTER Citizen Advisory Committee set up by their BOS Bd of Supervisors to get 'citizen input' into decisions about DATA CENTERS affecting them. The meetings were being hijacked by the DATA CENTER head honchos so that the citizens couldn't get action steps passed to deal with Prince William Co becoming the 'DATA CENTER capital of the world'.

Fredericksburg Residents chipped in their own money to fund a $400.00 FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) request to determine who was the developer behind the CVA Project. That's the 'Celebrate Virginia' 8-12 DATA CENTERS going in through the Council's 'aggressive' (city's own word) timeline to get the Technology Overlay District/TOD passed for that area of Fredericksburg 22401.

Rather than keep DATA CENTERS in Industrial Zones, the current Council was pressured to pass the TOD so that the 8-12 DATA CENTERS are within 200 ft of residential for families with children in the apartments as well as seniors in 'Jubilation'.

The 12-9-24 JLARC Joint Legislative Audit Review Committee says that DATA CENTERS in Virginia should be located in Industrial parks and kept away from residences at least 1000 ft.

The current Councilors: Susanna Finn (controversial Ward 3) appointee who voted twice to pass DATA CENTERS near residents as a Planning Commissioner and appointee, Chuck Frye, Jon Gerlach, Jason Graham, Jannan Holmes, Will Mackintosh and Mayor Kerry Devine played up DATA CENTER money for the public schools, the children, we need the money for the children, their future' to rally the PTA mommies and Mayfield residents to sell out the marginalized families in the apartments whose children will be exposed to the constant noise of the data centers every single day that they live there.

Prince William residents report that there are data centers within 200 feet of their home, and their children now have headaches and struggle to sleep at night.

There is only beginning baseline data being collected now, funded by non-DATA CENTER industry money, of bee and butterfly behavior near the Prince William DATA CENTERS Digital Gateway. So the negative effects of living within 200 ft of DATA CENTERS is just now being explored.

Again, the JLARC report says 'locate DATA CENTERS in Industrial zone, 1000 ft away from residents'.

The 2-25-25 Technology Overlay District/TOD was not supported by the Friends of the Rappahannock, yet these complicit Councilors passed it BYRIGHT, not even with a Special/Conditional Use Permit as 22401 residents asked at the 22401 public comment mic.

Shortly after the TOD was passed, American Rivers listed The Rappahannock River as the 6th Most Endangered River in the US.

The Councilors Done-Deal vote of 7-0 indicates another backdoor, non-transparent deal by these Councilors.

Perhaps when more studies come in over the decades, we will learn of the negative effects of DATA CENTERS on the vulnerable ones who have to live near them, including the disenfranchised children and their families and seniors.

Must be the privileged ones' option to vote on how others have to live with the constant noise of DATA CENTERS 200 ft away from their backyards.

It would be helpful for the FXBG 'Advance' to report on the complicity of this Council and its obvious mandate to aggressively pass the TOD on 2-25-25.

Do a FOIA of the 'Done Deal' 10-1-24 email from Curry Roberts, Fredericksburg Regional Alliance at the University of Mary Washington, including Councilor Jon Gerlach (Ward 2) with mention of ward 4 Councilor Chuck Frye's involvement to: 'begin socializing the benefits of potential data center development in the City of Fredericksburg'.