FROM THE EDITOR: Virginia's School Performance and Support Framework is Simply Horrid ...

... How do we know? By the things that the SPSF got right.

By Martin Davis

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Email Martin

If the goal was to make understanding what’s happening in Virginia’s public schools easier for everyone involved, then there’s no way to put a positive spin on the disaster that is Virginia’s new School Quality Profiles.

One simple example shows how poorly the SQPs explain what is happening in schools.

For 25 years, the state has used the word “Accredited” to refer to schools and districts that are meeting established academic goals. Makes sense, right? That’s what accredited means — someone or something has met a standard.

In the newly released — two months late — SQPs, however, Accreditation has nothing to do with students or teachers or hitting academic benchmarks. Now it measures whether districts are checking off bureaucratic compliance boxes. Literally. Teach core subjects? Check. School facilities safe? Check. Comprehensive plan? Check.

Even a 5th grader could see the confusion this is going to cause.

One would think Amy Guidera would have anticipated the problem and tried to come up with different terminology. But this is the same Education Secretary appointed by Gov. Glenn Youngkin who has overseen the botched rollouts of the Virginia Literacy Act and History Standards, to name but two poorly executed policy priorities, as well as a revolving door of Superintendents of Public Instruction — now numbering three in one four-year term.

Had Guidera asked a 5th grader for a better term than Accreditation, he or she might have come back with “Bureaucratic BS,” which isn’t the most eloquent expression, but at least parents would understand what’s being measured. Don’t like it? There’s always ChatGPT.

So if Accreditation says nothing about how schools are performing academically, what does? Hello, School Performance and Support Framework. (The name just rolls off the tongue, doesn’t it?)

Even on Substack, I don’t have the bandwidth to cover all the problems with SPSF (at least the acronym is easy to say) — starting with the fact that there’s no document spelling out the rules for calculating the results. “Just trust us,” one can see Guidera saying.

Not when proprietary systems are used to calculate some of the results — systems that people can’t access and check the math.

Virginia and states across the country have been trying to quantify academic success with ever increasing precision for the better part of a quarter century, each iteration worse than the last. Why would the SPSF be any different?

Still, it’s worth understanding why these SQPs are utterly indecipherable for the average citizen, confounding for data crunchers, and untrustworthy for educators. The key, it turns out, however, isn’t found in naming the legion of errors and fallacies associated with this mess.

Rather, the key is found in what the SPSF gets right.

From Hope to Horror

When then-President George W. Bush signed the No Child Left Behind Act in 2002, it was hailed as a blow to the “soft bigotry of low expectations.” And it came with a bold promise — tough standards and high-stakes tests would ensure every child in America would be at or above grade level in reading and in math by 2014.

Nearly a quarter-century on, it’s clear we are nowhere near that goal. What went wrong?

When it comes to educating children, statewide standards enforced by high-stakes testing will invariably leave many kids behind. District to district, school to school, the goals are the same — have children reading and doing basic math by 3rd grade — but how that gets done will depend upon the kids being taught.

Teachers with students who start school already reading and doing basic math face a very different set of challenges from teachers with students who come to school not reading and with no understanding of numbers. And teachers whose classes are a mix of both types of students — this is includes most teachers — face a different set of challenges still.

But rigid state standards give teachers little room to deviate from the rapid-fire pacing guides they must follow to cover everything the state mandates. Don’t understand diphthongs? Too bad, we have to move on. Scratching your head over long division? Sorry, compound fractions start tomorrow.

For kids who start behind or fall behind, there’s precious little space in the day to help her 1. Catch up, and 2. Stay up.

To the state’s credit, the new SPSF ratings recognize this problem and tried to adjust for it. Matt Hurt — head of the Comprehensive Instructional Program and one of the better educational data analysts in Virginia — said that the new system made “an attempt” to “balance proficiency/mastery, growth, and student readiness for the next level.”

In theory, such a system would reward schools by giving them credit for students who are reaching or exceeding the standard, as well as students who are showing growth over time even if they aren’t at standard. Finally, it would reward schools for having students ready for the next step.

The SPSF is so convoluted, however, that the reporting on this leads to grossly misleading tags that make little sense.

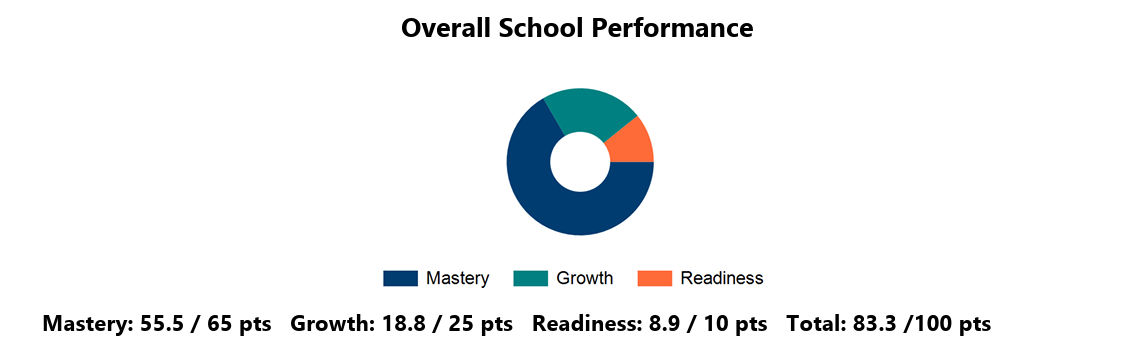

Consider how the state scores Battlefield Elementary School in Spotsylvania.

The state assigns points for students who have reached mastery, growth, and readiness goals. At Battlefield, the school earns a very respectable total score of 83.3 — that’s good enough to earn the second-highest of four performance category ratings — “On Track.” Except, that’s not what the school earned.

Here’s how the state reports Battlefield Elementary’s educational progress in the newest School Quality Profile:

Accreditation Designation: Fully Accredited

Performance Category (SPSF): Off Track

Federal Identification Status: Targeted Support and Improvement

How does a fully accredited school whose total performance score earns it an “On Track” rating get designated as “off track” and in need of “targeted support and improvement”?

It’s accredited because the school checked “Yes” on all 124 boxes dealing with compliance issues. So, too, it’s worth noting, did Spotsylvania Elementary with a total performance score nearly 10 full points lower than Battlefield’s.

Battlefield Elementary’s total performance is rated Off Track because one subgroup — students with disabilities — performed below VDOE-identified thresholds. Consequently, the entire school is federally tagged as needing Targeted Intensive Support.

Hence, in spite of earning an On Track score, the school is docked a full performance rating level because one subgroup is struggling.

Data accurately presented should tell a coherent story. There is nothing coherent or intelligible, however, about the story this data tells about Battlefield Elementary School.

Consequently, what should be a story of hope and positive outcomes at Battlefield Elementary becomes a list of massaged data points that read like a horror story.

Why design such a system?

Because this reporting mechanism was created not to celebrate or motivate or point the way toward academic achievement, but to award bureaucracy and punish the people charged with educating our children.

Built to Fail

Virginia’s new School Quality Profiles rest on two cornerstones.

First, it rests on the belief that there is a list of compliance issues— scored in the SQPs as “Accreditation” — that will lead to academic achievement.

Second, any academic struggles within a school reflect academic struggles across the school.

Compliance issues include things like promotion and retention policies, graduation requirements, offering courses students need for graduation, etc, and the state has had them for a number of years. There’s nothing inherently wrong with compliance standards. Yes, schools should follow best practices for a number of bureaucratic issues.

What the state can’t show, however, is that compliance issues lead to academic achievement. In reality, there isn’t a shred of evidence to back up this belief.

It leads one to wonder why the state doesn’t simply drop the compliance reporting in the SQPs. It’s an internal issue — keep it internal.

The greater issue, however, is the punitive nature of the SQPs.

Downgrading an entire school because one subgroup is struggling is akin to a teacher docking an entire class a full letter grade because one subgroup performed poorly on an exam.

Rather than helping parents better understand how their school is performing, this system hands ammunition to politicians and parents to pick apart public education. In short, this system is designed to shame, not strengthen.

That doesn’t surprise. Gov. Youngkin has from Day 1 attacked public schools and their teachers as well as public education.

The Answer Isn’t Standards, Tests, or SPQs

The question that we must ask is this. What does a successful public school system look like?

That question is easier to answer at the lower grades than at the upper grades.

Few would argue that it is critical that students are reading at grade level by the time they reach 3rd grade — preferably much sooner. And it’s critical that students have solid numeracy skills as they enter middle school.

Create solid tests to measure students’ efforts toward those goals, report out the scores, and use that information to help schools that aren’t making the grade.

But by the time one reaches high school, those questions should be in the rearview mirror. What happens in the classroom at this level should build upon the foundational skills learned in the lower grades,

Students should be wrestling with conflicting information, applying mathematical concepts to open-ended problems, reading complex literature, and expressing themselves eloquently in writing. These are higher-level thinking skills that cannot be easily measured by an exam or faithfully reported in data sets.

Rather, schools should be examined for how well they prepare students for what’s coming next.

This is something else that the SPSF aims to do, and it’s potentially one of its strengths, says Hurt.

But SPSF doesn’t deliver here, either. Across Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania, and Stafford, every high school save one — James Monroe High School — is rated Distinguished or On Track. JM misses the On Track cut line by mere two-tenths of a point.

But half of Spotsylvania’s elementary and middle schools are rated off track or worse, and in Stafford nine schools have the same rating.

Are we to believe that the feeder schools for local high schools are struggling, and the high schools are soaring?

More likely the SPQ’s overly complicated grading system is distorting what is happening on the ground.

Why?

The answer isn’t all that complicated. Students are not widgets, and education is not an assembly-line business. This makes rigid standards and high-stakes testing the wrong fit for measuring student achievement.

The more sophisticated the measurement systems become, the more painfully apparent the inability of data to accurately capture learning becomes.

Virginia was the first in the nation to tie rigid standards to high-stakes testing; Virginia should be the state that bucks the trend and abandons them. Instead, let’s embrace an approach to learning that emphasizes skills development and uses tests to support individual students, not give politicians and critics hammers to beat the public school system with.

The time to do this is now.

Donald Trump is ending the Department of Education and the few dollars it sends states’ ways. Thus, federal interference in state education systems is weaker than it has been since NCLB passed.

Abigail Spanberger is a passionate supporter of public education and understands the importance of supporting teachers and local schools as opposed to testing them ad nauseum.

In education, data isn’t the end-game. And the SPSF proves it like no other assessment system before.

It’s time to get up and walk out of this horror show, and into the light that is focused on motivating children, building their skills, and truly preparing them for the world that is ahead of them. Not the next test whose only purpose is to undermine public education by obfuscating, instead of illuminating, student achievement.

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit the link that follows.

Support Award-winning, Locally Focused Journalism

The FXBG Advance cuts through the talking points to deliver both incisive and informative news about the issues, people, and organizations that daily affect your life. And we do it in a multi-partisan format that has no equal in this region. Over the past year, our reporting was:

First to break the story of Stafford Board of Supervisors dismissing a citizen library board member for “misconduct,” without informing the citizen or explaining what the person allegedly did wrong.

First to explain falling water levels in the Rappahannock Canal.

First to detail controversial traffic numbers submitted by Stafford staff on the Buc-ee’s project

Our media group also offers the most-extensive election coverage in the region and regular columnists like:

And our newsroom is led by the most-experienced and most-awarded journalists in the region — Adele Uphaus (Managing Editor and multiple VPA award-winner) and Martin Davis (Editor-in-Chief, 2022 Opinion Writer of the Year in Virginia and more than 25 years reporting from around the country and the world).

For just $8 a month, you can help support top-flight journalism that puts people over policies.

Your contributions 100% support our journalists.

Help us as we continue to grow!

This article is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. It can be distributed for noncommercial purposes and must include the following: “Published with permission by FXBG Advance.”

Even before the Youngkin Virginia Dept of Education rolled out its Virginia's School Performance and Support Framework, subgroup SWD/Students with Disabilities affected a school's performance. That's why building admins are reluctant to accept self-contained classrooms with students with significant disabilities, such as moderate intellectual disabilities or complex multiple disabilities. And sure, some brave building admins are willing to try it and take the sweat/heat, at least until their scores fall to 'at risk'. Spotsy Co PS has enough schools that these students and their teachers are moved around frequently, so their test performance doesn't impact a school's rating too much.

Imagine being the teachers/staff in these classrooms. Classroom packed up in May expecting to return in August to the same room but getting a last-minute notice during the back to school week.

That's the week that other sped and the gen ed teachers can participate in their professional development, renewing friendships at the extended lunch time, off campus to flood local restaurants to talk about the summer break, but you're busy sorting out what furniture belongs to the program that funded it: the sped program or the school building's property.

Then stuck waiting for the truck to show to load up the furniture and the boxes, or use your own car to transport furniture and teaching supplies back and forth between the schools because the truck is taking too long to show, and Friday is Open House.

There's finally the actual move to an empty room that's been found in a strong Pass rate building on Day 2 of that week, or even worse, Day 4, later, which means set up a room in one building for Open House Friday but as soon as the last parent leaves, start packing up the room again, come in on the weekend to finish packing it up for a truck move to have it set up in another school by first day of school on Monday.

Notice to parents? yeah it's written. but surprise to them! Your child is going to have a longer bus ride to their new school.

That's not fair. Some parents do ask, What about being able to attend the neighborhood school like typical students, without these disabilities? But if you have an outstanding teacher, you're going to follow that program's new location.