History Thursday: 108 Charlotte Street

This building, associated with local dentist and civil rights leader Phillip Wyatt, was moved to this location from Princess Anne Street in 1977.

By Adele Uphaus

MANAGING EDITOR AND CORRESPONDENT

Email Adele

On September 7, 1977, this brick house—weighing 190 tons, and wrapped in steel cables—was loaded onto a dolly and pulled two blocks from its original location on Princess Anne Street to where it stands now.

The move to Charlotte Street ended two-years of negotiation between the U.S. Postal Service and Historic Fredericksburg Foundation to prevent demolition of the house, which was originally built in 1846. The postal service acquired the house from owner Phillip Wyatt, as part of a large parcel it was eyeing for the location of the new city post office.

According to a narrative by the Historic Fredericksburg Foundation, the entire parcel was located within the Fredericksburg National Historic District, but the “Gravatt House,” as it was known, was the only building “of historical and architectural significance” on the site.

The Board of Historic Buildings blocked demolition of the structure in December of 1974 and suggested that it be moved to a new location, according to a Free Lance-Star article, but City Council in January of 1975 “rejected the board suggestion for use of city property” as a new site.

The result of lengthy negotiations between all the parties was that the post office agreed to donate the building to HFFI and pay for the cost of its relocation to HFFI-owned property, if the organization would plan and carry out the move.

The exterior of the building today bears an HFFI marker calling it the “George Gravatt House,” after the original builder, who was a carriage maker and whose family owned the house for a century.

But it also bears a marker for Phillip Y. Wyatt, who practiced dentistry in the building from 1952 until 1975, and who was also a civil rights leader and 25-year official of the local and state NAACP. He was also co-chairman of the city’s Biracial Commission and a member of the Virginia State advisory committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights.

On June 6, 1950, Wyatt was one of the leaders of an early Fredericksburg civil rights protest, staged by members of segregated Walker-Grant High School senior class and the local NAACP. The class had asked to hold its graduation ceremony at the Fredericksburg Community Center, and was granted permission—provided they enter and exit through a side door, not the front door.

In protest, class members marched through the streets and held a demonstration in in front of the Center, singing songs and holding signs reading “This Entrance Closed to Us.” Wyatt, as NAACP secretary, presented dummy diplomas to two seniors, telling them they were “learning at the outset that life is filled with problems which we will solve in an orderly and intelligent way,” according to a Free Lance-Star article.

Wyatt told the Free Lance-Star that the issue of equal access to community spaces was an issue the Black community “cannot afford to let die.”

“It’s not simply a matter of getting a place to hold the commencement,” he said. “It’s the principle of being asked to use the backdoor. I feel it is a sort of insult… I don’t think the issue is dead.”

Later that same summer, the NAACP requested use of the Center for a meeting, only to be told five days later by the city’s Recreation Commission that their request conflicted with a “youth canteen” for white teenagers. Wyatt, according to a Free Lance-Star article, raised concern about how long it took to the Commission to respond to the NAACP’s request.

Wyatt also encouraged local NAACP members to take a more active role in securing their civil rights, telling membership at an August 1950 meeting that “the time has passed when the citizens of Fredericksburg can depend on upon [legal teams from other counties] to fight our battles.”

Later on, Wyatt began working on the issue of desegregation of Fredericksburg’s schools. In June of 1955, he told the Free Lance-Star that the local NAACP chapter would ask the Fredericksburg School Board for a “progress report” on integration efforts. He pointed out the board’s official silence on the topic and said, “There should be some effort to find a solution to the problem, and the only way is for the School Board to discuss it.”

In July of 1955, the School Board voted in a special called meeting to adopt the state-recommended policy to operate segregated schools for the coming year.

But Wyatt continued to press for change. He talked about his belief in desegregation and integration—and that it must be legislated—in 1957, when he was elected state president of the Virginia NAACP. “Desegregation is to eliminate legal restrictions and make it possible to study and work together,” Wyatt said, according to an Oct. 11, 1957, Free Lance-Star article. “Integration certainly must come later. It means the white child understanding the colored child.”

In May of 1964, the NAACP sent a petition calling for immediate steps to desegregate the city’s public school system. By that time, the School Board had adopted a “free transfer” policy, which gave students the opportunity to attend the school of their choice, but Wyatt told the newspaper that this policy placed too much of a burden on parents.

The petition was signed by 499 city residents—including NAACP members and non-members—and it called for desegregation of the “student body, faculty, custodial and administrative offices.”

The School Board’s response was that “the system here was being administered “in accordance with with federal and state law and that admissions were being denied on the basis of race,” according to a July 3, 1964, newspaper article. Wyatt told the paper that the NAACP would consider litigation.

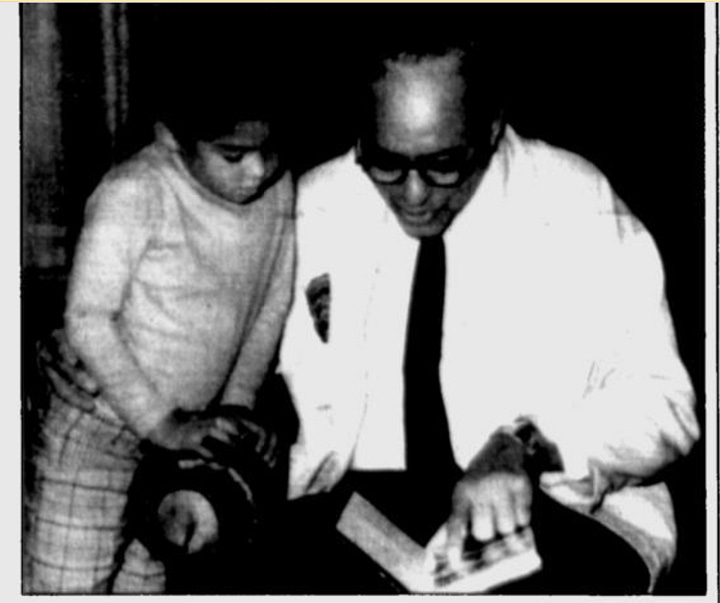

In addition to pressing for change on his own, Wyatt mentored Fredericksburg youth through their 1960 campaign to desegregate the city’s lunch counters, according to a 1992 Free Lance-Star article.

Phillip Wyatt died in 1984. In 1992, HFFI and Shiloh Baptist Church (Old Site), celebrated his legacy as a tireless fighter, counselor, and role model by placing a marker in his honor on the building that housed his dental office

In 1996, his grandson, Adam Wyatt, bought the renovated “Gravatt House” and relocated his own dental practice there.

Today, the building houses a law office.

Support the Advance with an Annual Subscription or Make a One-time Donation

The Advance has developed a reputation for fearless journalism. Our team delivers well-researched local stories, detailed analysis of the events that are shaping our region, and a forum for robust, informed discussion about current issues.

We need your help to do this work, and there are two ways you can support this work.

Sign up for annual, renewable subscription.

Make a one-time donation of any amount.

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit the link that follows.

This article is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. It can be distributed for noncommercial purposes and must include the following: “Published with permission by FXBG Advance.”