Sunday Books & Culture - A Special Essay from the Editor on Liberty and Freedom of Speech

At Montpelier, James Madison could see future hope, present inequalities, and the throughway to liberty -- Education and Free Speech.

By Martin Davis

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Email Martin

Standing on the porch of Montpelier — the home of President James Madison — and, looking at the panoramic view of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the distance, one can ponder how Madison might have imagined America’s future.

The horizon from his front porch pointed toward the nation’s future, and the opportunities ahead on the land that Lewis and Clark had explored and cataloged less than a decade before Madison moved into the White House.

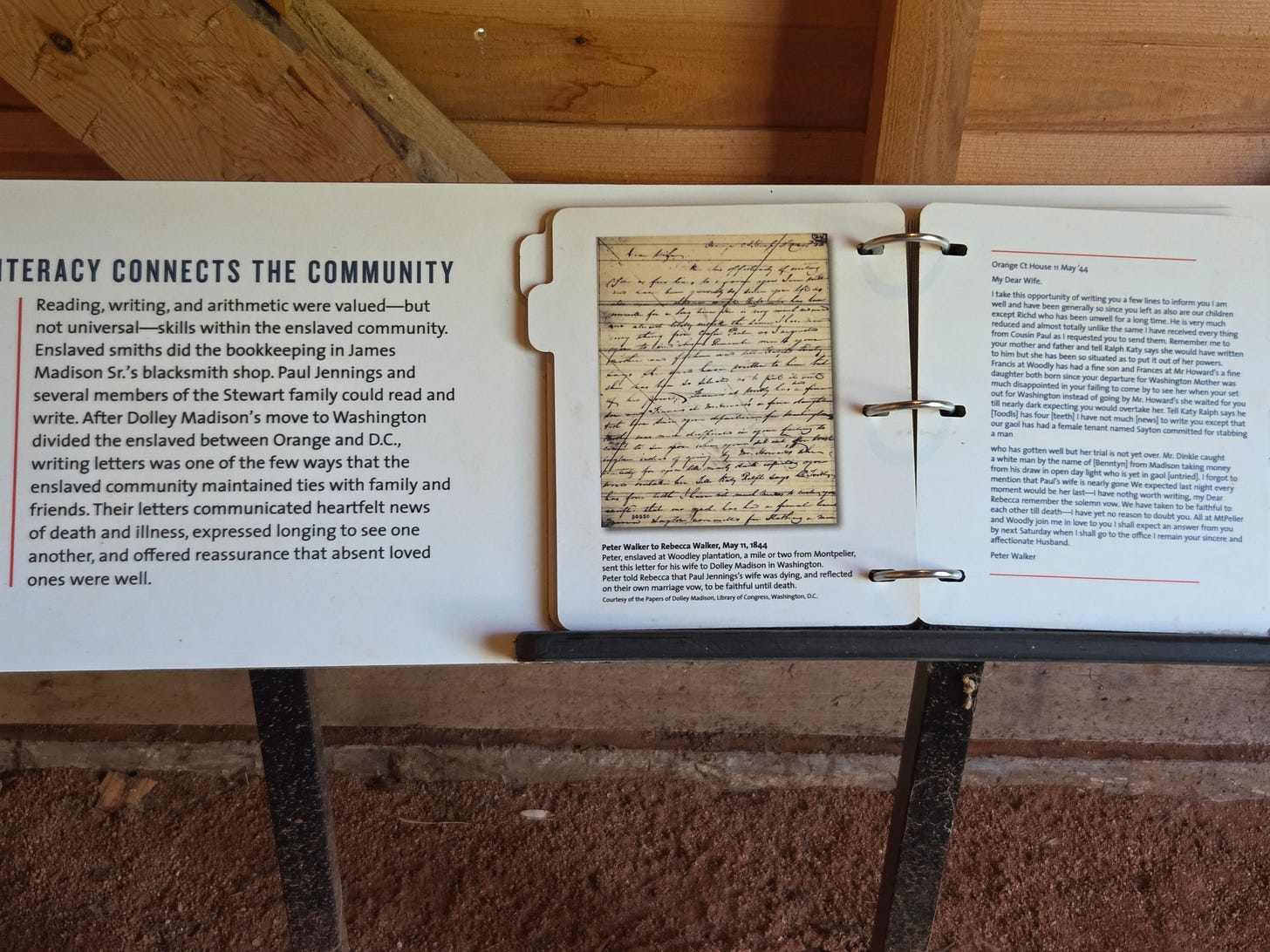

From that same porch, however, the challenges the nation faced were also before him. At any given time, Montpelier was run by roughly 100 enslaved individuals. The institution deeply conflicted Madison, who understood the inherent contradiction between liberty and slavery, but never himself granted liberty to those on his plantation.

Writing to the Marquis de Lafayette in 1820, Madison recognized “the dreadful fruitfulness of the original sin of the African trade.”

Madison similarly struggled with how to handle the Indians who were being displaced by westward expansion. He had hoped that Indians would assimilate and adapt to farming and European education, and he recognized that Indians had title to their land. Nonetheless, he pressed westward expansion that displaced Indians even as he had strong misgivings about the more-violent methods adopted by Americans in dealing with the removal.

Over the past five decades, remarkable efforts by historians, journalists, and many others have brought to light the great moral questions of American expansion, our “original sin,” and our brutal treatment of Indians.

That progress is being actively fought against in the name of avoiding “divisive concepts” in the language of Gov. Glenn Youngkin in Executive Order 1, of embracing “parents rights” in the language of two current and two former members of the Spotsylvania County School Board, and of ending “improper partisan ideology” in the language of President Donald Trump.

It’s hardly a new effort. And it’s certainly not the effort of one political philosophy or party. As Columbia professor Mark Lilla has documented and critiqued so eloquently, when faced with the opportunity during the rise of Ronald Reagan to “to develop a fresh political vision of the country’s shared destiny,” liberals, instead, “threw themselves into the movement politics of identity, losing a sense of what we share as citizens and what binds us as a nation.”

The effect of suppressing “divisive concepts” and leveraging “identity politics” to marginalize and silence those who seek a more unified vision of who we are as a people is the same — a stilted story of America that effectively marginalizes half our citizens.

The suppression of speech, and the curtailing of liberty is the consequence.

There is an anecdote to our ugly politics. And it’s discovered, as my founding partner here at the Advance, Shaun Kenney, is fond of saying, by “learning to breathe with both lungs.”

Politics, however, is ill-devised to help us do that.

Madison knew that, too.

Education, the Father of the Constitution understood, is the only sure way to instill liberty. And true education — that measured by the growth of human morality, and not by the rise on high-stakes exams — depends upon free speech.

Writing to Thomas Jefferson in 1823 referencing the University of Virginia, Madison said: “... you do not overrate the interest I feel in the University [of Virginia] as the Temple thro' which alone lies the road to that of liberty.”

Open discourse, humility, and respect — these are the ingredients that define a healthy education. These are also — in the hands of an educated citizenry — what make American democracy function.

Two books do an extraordinary job of helping us appreciate this truth, as they encourage us to spend less time engaging in bloviating, self-serving social media arguments over politics, and more time learning to wrestle with the American story.

It is a story that cannot be reduced to simple facts — as we are seeing in real time, many “facts” can, and are being, erased. Rather, it is a story of what happens when a commitment to true education is crossed with the ideal of liberty. It is the story of human growth, and the broadening of respect for everyone on which American democracy rests.

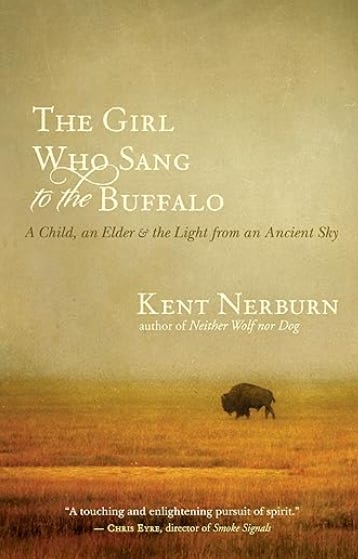

The Girl Who Sang to the Buffalo is the third in a trilogy of books by Kent Nerbern telling of his experiences with Lakota Indians Dan, Jumbo, Gordon, Yellow Bird, and Zi on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, and an old Ojibwa Indian, Benais, who calls them all to northern Minnesota to discover what happened to Dan’s sister, Yellow Bird, who was swept away to an asylum for Indians and never heard from again.

The power of this story, and in the two that preceded it — Neither Wolf nor Dog, and The Wolf at Twilight — is found in the struggles of people who share little in common to understand, respect, and live among one another.

Kent Nerbern, the writer, struggles throughout the trilogy to understand Indian culture. And in this third installation, his ability to understand, respect, and ultimately trust that which he can’t fully grasp is put to severe test.

By the end, Nerbern has not become “Indian,” nor have the Indians embraced Nerbern’s European culture. But the people have learned to respect and learn from one another.

As Nerbern describes the experience of writing the trilogy:

For more than two decades I have tried, honestly and respectfully, to walk the difficult line between the world of Native America and the world of those of us whose people came, willingly or otherwise, to these American shores. I have done this because I believe that we, as Americans, are poorly served by our willful avoidance of the true facts of our national experience, and also because I believe that the lives and ways of the Native American peoples have much to teach us all.

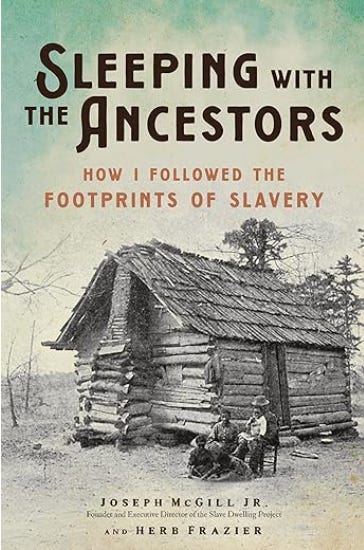

Sleeping with the Ancestors takes a similar trajectory. The author, Joseph McGill, chronicles his experiences of sleeping more than 200 nights in the cabins of slaves.

The stories he relays are raw. For example, he does not use the term “enslaved” to described those owned by whites, but rather “slaves,” because it’s his “desire to be as frank as possible and not sugarcoat American history.”

The book’s purpose, however, is not to have readers coming away feeling as if they better feel the pain slaves endured. Nor to make the ancestors of those who owned slaves feel remorseful for their ancestors’ actions.

“My simple act of sleeping where enslaved people slept has broadened my awareness of their history, but it cannot replicate the pain and suffering they endured,” McGill wrote. “I hope that my travels have brought attention to the need for a deeper study and understanding of this history.”

Madison would have understood, and embraced, what these writers were trying to do. At least, we can imagine that he would when standing on his porch.

Not looking across to the mountains and opportunity, not looking to the enslaved on his plantation and inequality, but standing in the right corner of the porch, and looking toward the pond. Between the porch and pond stands a “temple,” built around 1810.

Education grounded in open discourse, humility, and respect has been run over roughshod by left and right politicians for decades.

The Girl Who Sang to the Buffalo, and Sleeping with the Ancestors, can help us rediscover what Madison surely stood on his porch and pondered — future hopes, present inequalities, and the truth that education grounded in free speech is what delivers liberty.

Sleeping with the Ancestors: How I Followed the Footprints of Slavery

Paperback: $16.19 at Amazon

Kindle: $11.99

The Girl Who Sang to the Buffalo: A Child, An Elder, and the Light from an Ancient Sky

Paperback: $19.95 at Amazon

Kindle: $9.99

Rest of text

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit the link that follows.

Support Award-winning, Locally Focused Journalism

The FXBG Advance cuts through the talking points to deliver both incisive and informative news about the issues, people, and organizations that daily affect your life. And we do it in a multi-partisan format that has no equal in this region. Over the past year, our reporting was:

First to break the story of Stafford Board of Supervisors dismissing a citizen library board member for “misconduct,” without informing the citizen or explaining what the person allegedly did wrong.

First to explain falling water levels in the Rappahannock Canal.

First to detail controversial traffic numbers submitted by Stafford staff on the Buc-ee’s project

Our media group also offers the most-extensive election coverage in the region and regular columnists like:

And our newsroom is led by the most-experienced and most-awarded journalists in the region — Adele Uphaus (Managing Editor and multiple VPA award-winner) and Martin Davis (Editor-in-Chief, 2022 Opinion Writer of the Year in Virginia and more than 25 years reporting from around the country and the world).

For just $8 a month, you can help support top-flight journalism that puts people over policies.

Your contributions 100% support our journalists.

Help us as we continue to grow!

This article is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. It can be distributed for noncommercial purposes and must include the following: “Published with permission by FXBG Advance.”

I recently learned who Charlie Kirk was. Hand to God, I always thought that meme of a guy sitting under a tent with coffee demanding to be proved wrong was just that, an internet meme.

And somehow, I lived my life in blissful ignorance up until a week or so ago with that illusion.

Though I admit, I was not exactly shocked when I learned otherwise. A millionaire paid a fast talking young man to show up on college campuses and to "debate" students there, and selectively publicized the results when he "won".

After hearing the moaning, threats, and wailing from those who typically claim their form of humor is Andrew Dice Clay, Richard Pryor, etc. I figured I'd go on an find out what all the fuss was about, if we were going to use Air Force Two to move the guy, have a national day of mourning on par with 9/11, and were giving out pink slips to any public entities who were not immediately publicly rending their clothes and covering their heads in ashes.

What I found, in the limited amount of time that I looked, was a guy using some pretty weak methods against children, then when they were unsuccessful in convincing him to change his mind, counting that as having "won".

I also noticed that some of the givens he was using made it pretty much impossible for him to lose. You had to take it as a given that his chosen version and interpretation of his Bible was the basis of the debate. If I got to set that up as the parameters, rather than peer reviewed studies, I believe I could win most arguments too. Or at least never have to claim defeat.

I'd say that summarizes reality tv in a nutshell.

Likewise, the conclusion given in this article seems similarly preordained. If you had pre-determined that was what you would find.

Yes, I suppose if you stand at Montpelier, on a certain corner, and maintain your focus on a certain symbolic building - you can ignore both the promise of a future of hope, and the reality of a cruel present - if doing so allows you to maintain that focusing on that chosen symbol is all that matters - and therefore there is no need for you to either face the realities of the present, nor plan for the future.

Never to find a value worth committing to nor defending in the present, because all are guilty.

It's a safe path.

I note that when chastising Democrats for "identity politics", another term I had to look up, it turns out to be when people identify themselves as individuals, rather than merely obedient cogs of the state. Not quite sure how that is harmful, though apparently, like the late Mr Kirk, Mr Davis takes it as a given that it is harmful and on par with the current active Republican efforts to wage war on Democrats, erase anything which does not support a monolithic, Republican approved history of our nation.

How the two are truly the same, is beyond me.

I guess its equivalent to the skill of being able to go to a slave labor camp, not hear the cries of the slaves, ignoring the policies you're also enacting to enslave and disinherit others who owned title to the land before you, while gazing upon a temple of dreams built by the hands of those you own.

Or coming to that temple centuries later, and using that vision to justify minimizing the harms being done in its name in our own time.

Again, I'm afraid I lack the vision. Upon reflection, not sure I want it......