FROM THE EDITOR: Our Local Schools Have a Superpower - Multilingualism

By Martin Davis

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Email Martin

For the third time in the past 20 years, the United States is facing the prospect of entering a war in a Middle Eastern nation that speaks a language very few U.S.-born Americans understand. In the case of Iran, that language is Persian (Farsi). It’s not the only language spoken in Iran. According to the CIA Factbook, Azeri and other Turkic dialects, Kurdish, Gilaki and Mazandarani, Luri, Balochi, and Arabic are also commonly spoken.

As we continue to find ourselves engaged in Middle Eastern conflicts, it is imperative that we do a better job of understanding not only these countries’ histories, but their languages as well. Failure to do so to this point has created issues for the U.S. government over the past quarter century.

In the wake of the September 11, 2001, attacks, the U.S. government did not have nearly enough Arabic-speaking government employees to deal with the pressing need to translate intercepted communications.

As late as 2017, a GAO report found that “23 percent of overseas language-designated positions (LDP) were filled by Foreign Service officers (FSO) who did not meet the positions’ language proficiency requirements.”

The lack of interest among U.S.-born, monolingual English speakers in learning foreign languages is well-known. “America-first” policies are only worsening the situation. And yet, a sizeable subset of Americans have long understood and valued multilingualism, whether their appreciation is based in humanitarian terms, business terms, or educational terms.

The challenge has been getting everyday Americans to embrace the value of learning to speak more than one language.

Nationally, our unwillingness to embrace multilingualism usually becomes an issue only in times of national distress — such as the bombing of Iran this weekend.

Locally, however, our failure to embrace multilingualism is creating challenges for our communities right now. For our schools, to be sure, but also for our businesses and community cohesion, as well.

The reason is simple — more families are speaking a language other than English at home. This hinders first- and second-generation immigrants academically, as they tend to struggle more in school. But it also costs businesses money because they struggle to attract these citizens.

Fredericksburg and Stafford are both above the state average of 17.8% of people who speak a language other than English at home (Fredericksburg - 18.2%; Stafford County — 19.2%). Spotsylvania at 15.4% is below the state average, but that percentage is climbing rapidly.

Mandating more language education in schools will not resolve this problem. These classes have for decades seen declining enrollments coupled with difficulties finding people qualified to teach them.

Schools do, however, hold the key to helping the up-and-coming generation break the monolingual rut.

English Language Learners Hold the Key

The key to growing interest in learning foreign languages are the ever-growing number of students in our schools who already speak a foreign language. Tapping their language skill could potentially grow the number of monolingual English-speaking students who become bilingual. More important, it could also have the benefit of helping English Language Learning students becoming fluent in English sooner.

To understand how, it helps to examine the number of ELL students currently enrolled in our school systems.

In our three local public school districts — Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania, and Stafford — one can find students who speak Farsi, Spanish, Arabic, Portuguese, Hindi, Vietnamese, Urdu, and at least another 35 languages.

How many students in our school systems speak a language that isn’t English is difficult to nail down, but we can use the number of English Language Learners to get an idea.

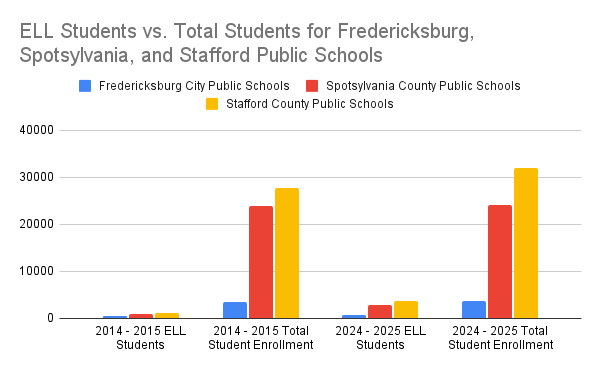

In Spotsylvania County Schools, there were 2,773 ELL students in 2024-2025 according to the Virginia Department of Education — about 12% of the total student population — who collectively represent more than 40 language groups.

Fredericksburg City Schools had 836 ELL students, or about 23% of its total student population. And in Stafford County Public Schools, there were 3,626 ELL students, or just over 11% of the total student population.

The number of ELL students in our schools has surged over the past decade.

This growth in ELL students has typically been deemed a problem. These students have consistently underperformed their peers for whom English is their first — and often only — language on state standardized tests, raising concerns about how effectively ELLs are being educated.

The thinking for addressing this problem is to improve these students’ English proficiency via more-traditional classroom instruction.

But taking classes in English is a slow way to master our language.

Immersion is the best way to help students learn English, and that’s part of the thinking behind Virginia drastically reducing the time ELL students have to come up to speed on becoming English-efficient from 11 semesters to three.

However, simply reducing the time students have to learn English is unlikely to prove successful. Getting students up to speed quickly via immersion would require general education teachers to be capable of aiding with the transition.

Presently, our teachers are poorly equipped to deal with ELL students in their classrooms, according to a new study from the Rand Corporation. Among the high-level findings:

Addressing the needs of Multi-Language Learners ranked low among principals' priorities for selecting teachers' professional learning and instructional materials, even in schools with a moderate to large proportion of MLLs.

Slightly less than one-third of teachers serving MLLs reported that their curriculum materials were adequate for helping MLLs master their state standards and language in English language arts, mathematics, and science.

About 60 percent of teachers reported a moderate or major need for more or better curriculum materials that provide options for MLLs.

Helping teachers prepare for these students and having adequate materials is an admirable goal, but not a pragmatic one in any near-term scenario.

A quicker solution to improving ELL’s gaining influence is to enmesh them with their English-only-speaking peers in their schools.

ELLs Not as Problems, but As Solutions

Forcing children to intermingle who don’t share a common language, culture, or interest is fraught with difficulties. People naturally gravitate toward those whom they have things in common.

Wedding the need to help ELLs learn English to the need for Americans to become bilingual is a way to break down the natural tendency to interact with people from one’s own culture.

The pathway to making this happen? Make ELLs prominent partners in teaching monolingual Americans a foreign language.

There are multiple advantages to such an experiment.

ELL students teaching monolingual English speakers allows them to play a prominent, constructive role in their educational environments. In an environment where every day can feel like failure as one tries to learn a new language, teaching others their native tongues would allow ELLs some success during the course of the day.

Learning from one’s peers is a powerful tool in any student’s arsenal. While skilled teachers are essential for framing learning and keeping things on course, peer learning can make acquiring a new language less threatening.

In an environment of teacher scarcity, schools must find creative ways to fill knowledge gaps. Native speakers properly leveraged can greatly extend the reach of a single language teacher.

Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania, and Stafford are no longer sleepy, rural communities. These are highly diverse, urban communities. While that may threaten some, it is an indication of the growth that has made this region so attractive to so many.

At a time when we desperately need more understanding and less America First, our ELL students can help lead our region into a healthier, and wealthier, future for all.

Support the Advance with an Annual Subscription or Make a One-time Donation

The Advance has developed a reputation for fearless journalism. Our team delivers well-researched local stories, detailed analysis of the events that are shaping our region, and a forum for robust, informed discussion about current issues.

We need your help to do this work, and there are two ways you can support this work.

Sign up for annual, renewable subscription.

Make a one-time donation of any amount.

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit the link that follows.

This article is published under Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. It can be distributed for noncommercial purposes and must include the following: “Published with permission by FXBG Advance.”

Thanks for this! Again, politicians making policies for educators,what could go wrong?

What they didn't consider when they went from 11 to 3 semesters is the students' families, more than likely, don't speak or read English yet, either. If the children aren't getting help by speaking or writing English at home, they have no chance to practice. How would these politicians do if they moved to Thailand but couldn't practice Thai after they left their classroom in the afternoon, had two months without instruction, then they had to take reading AND writing test in Thai on a graduate school level?